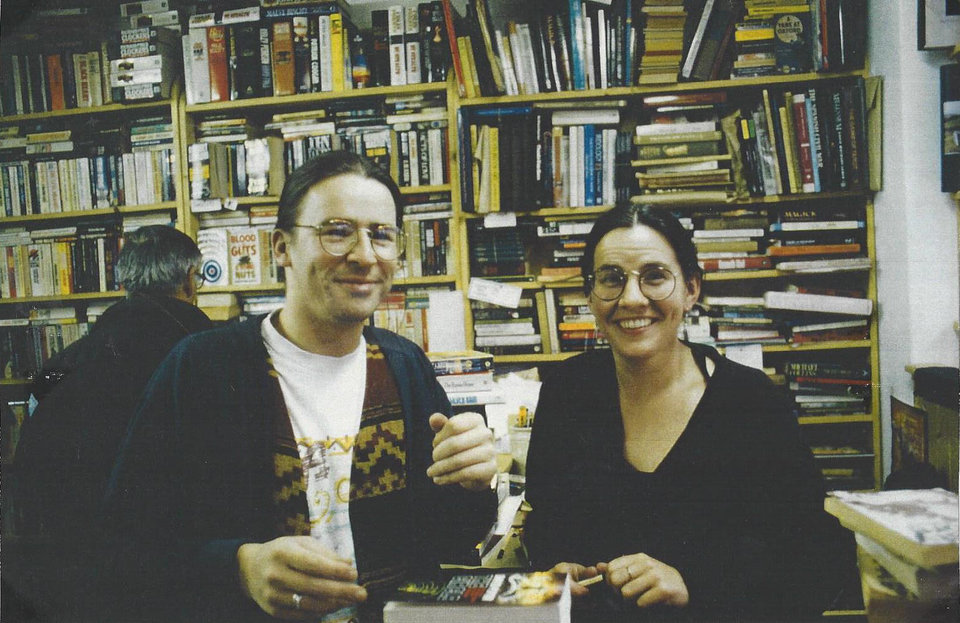

Vinny Browne – Bookstore Manager & Radio Presenter

Vinny is manager of Charlie Byrne's Bookstore & Presenter of The Arts Show on Galway Bay FM

More from...

How would you describe yourself?

I suppose I'd describe myself as optimistic, approachable, interested. A major difference between people a lot of the time is whether they're interested and engaged or not. I'm interested in people and what people are doing. I find that engaged trait very attractive in other people and it's something I like to nurture in myself. In a lot of ways, I'm a traditional person - pre-technological. I still write everything out longhand with a pen with paper and that's the only thing that will work for me. I have this idea that 1968 was a kind of a highpoint of civilisation and then after that, things started to slip uncontrollably. As soon as you get into the oil crisis of the 70s, life goes to hell (laughs). But I do like that kind of late 20th century analogue world; I think it had a lot going for it that we miss now.

Can you tell us a bit about your background?

I had a fairly typical generational pathway. I went to UCG in the 80s; I did a BA in English and History –which ensured I was totally unemployable in Ireland at the time. The 80s were tricky times here and everybody I knew was in London, so I went to London and spent a year and a half there working in HMV in Oxford Street, which was great fun. Pretty much everyone in the stock room where I worked was in a band. So the culture was going around watching other people's bands - that was a good time. I came back to Ireland in 1989. Around then, I used to spend a lot of time in Charlie Byrne's tiny little book shop on Dominick Street, a couple of doors down from the Galway Arms. There was only room for one staff member, otherwise there wouldn't have been any room for customers, but it was a great little shop. I used to go in and out of there and one day, I said to Charlie that I was looking for a job and he agreed to hire me. So it started from there. We didn't have a till at that time; the money from the shop was in a shoe box. So it was very market trader-ish.

You're almost 25 years in Charlie Byrne's. How do you feel about the bookstore, seeing as it's been such a major part of your life?

Great. I still think that I'm so fortunate to have joined a fledgling enterprise, as Charlie Byrne's was at that time, and it built up very organically. The bookshop grew with the city in many ways; it grew with the Arts Festival and Cúirt and all of those cultural festivals that we love the city for.

Is it a struggle for independent bookstores to survive at the moment?

It's always a struggle. People say that you never get into book selling to make money - you go into book selling to have the experience of selling books. It's almost a vocational thing. And it is enjoyable; it's almost worth not making a fortune in order to have those experiences repeatedly. I think that if an independent bookshop is still in business now then it will continue because it has survived the seismic changes in the trade of recent years. It has streamlined itself enough to adapt to the local need and it has a distinct personality that will ensure that people want to go there. Otherwise, they'd be gone already.

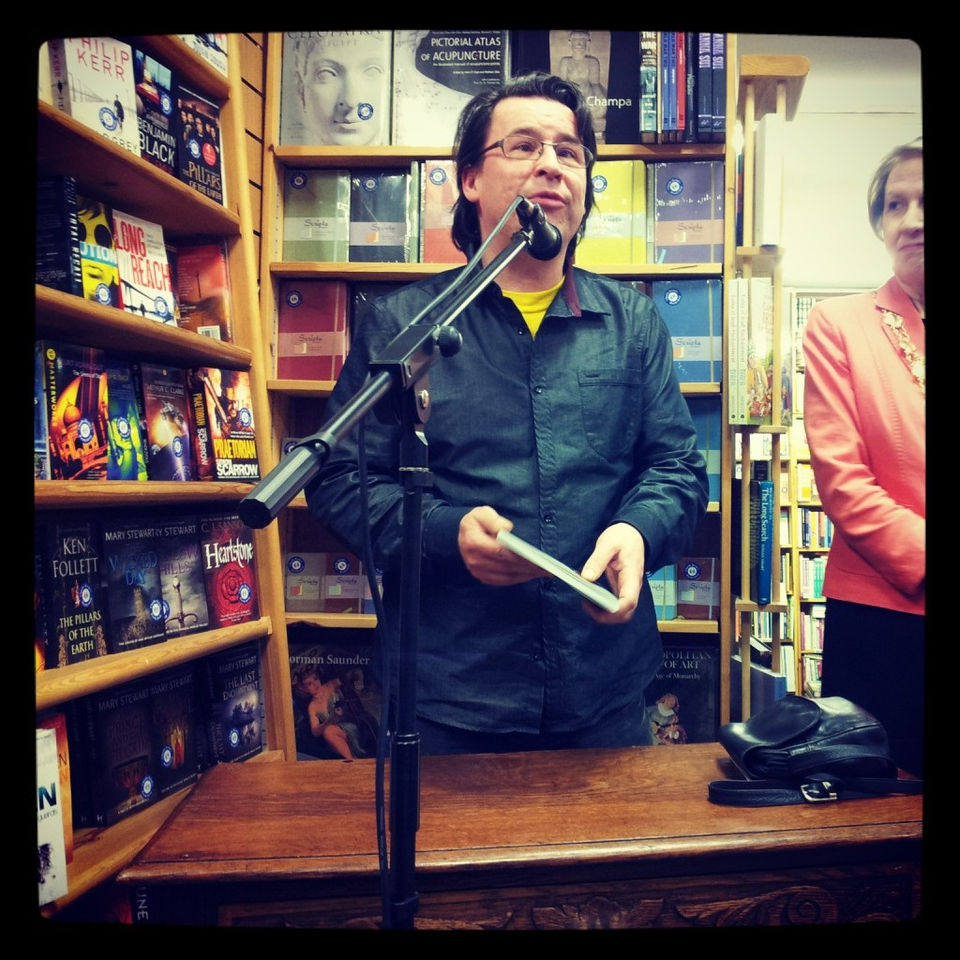

A thing we do more and more all the time is bookshop events - having things on. Making each person's visit to the shop as unique and as interesting as possible is the key to survival. The shop is the venue that gives you a unique experience that you can't replicate online. You can't enjoy somebody reading their work in a live setting while having a glass of wine in front of your computer screen at home. That's the kind of thing that turns it from being just another business into a cherished social and cultural space. That's the future.

Where do you see the future of the book with all the new technologies it's competing with?

I'd be very optimistic about how the book will continue in the world. It's very different from the way that the digital technologies have transformed other businesses like the music or photographic industries because the book has been around for thousands of years. The codex, where people figured out that the best way to transfer information was to fold over pages and stitch them in the middle and hand them to each other - that's been around since before the bible. People have a deep attachment to books. Even when people read something phenomenal on a kindle, one of those books that when you're reading it it changes your life, they go out and they buy the physical copy. I don't think anybody would have anticipated that even five years ago.

What's really interesting is the area of children's books. In the bookshop, for instance, the children's book section is more important now than it ever was, because parents want their kids to have that traditional engagement with the book that they grew up with themselves . We have a story time on Saturdays which is hugely successful and that end of the business is actually growing all the time. I think the whole culture of the book is still very strong. There's still lots of things that the traditional book can do that can't be done on an e reader. For instance, on a kindle, you can't flick back 30 pages to check a fact or a character's name without totally interrupting the reading experience

And you can't flick through the book and bend it and sniff it.

Yes, the whole tactile thing that is so central to the physicality of the book is hardwired into the culture and into our brains that we feel we actually need this and it's good for us and we like it. It's not going to change in the same way that people so readily abandoned the printed photograph or how they consume music.

What do you love about books?

Just the ability they provide to allow you teach yourself. If you're interested in something, the fact that there is a book written about it is a given. They are a continual means of self improvement. I would have read a lot of fiction in my teens, twenties and 30s but I've always liked nonfiction and long-form journalism as well. This shift is another thing that the technological revolution has compromised. That new journalism movement in the 60s and 70s and into the 80s in the UK isn't the same exciting place it used to be. It still exists but it's not supported in the same way and that always interested me - that big long form magazine journalism that you'd get in magazines like Rolling Stone or The Atlantic appears to have become a victim of our shortened attention spans.

How much of a role does literature play in your life.

There's very little work /life divide for me. Most of the time, if I'm in the shop, I'm dealing with literary matters, but if I'm out and about, that conversation continues. No matter where I am, people are talking to me about books and literature or whatever it is they're reading at the moment. And that's fine - I actually love that. People always say “I shouldn't be talking about work” but they continue anyway and that's exactly how I like it. I'm happy that I don't spend much of my time talking about golf or the latest Joe Duffy outrage.

It sounds like there's flow there - isn't that the cohesion that a lot of people are seeking in their lives?

There is flow there. I think I'm very fortunate not to live my life in compartments. The one problem about that is that it makes time go by extremely quickly. You go, ‘Where the hell is the time going?' because you're in a continual stream.

You also have your own show, on Galway Bay Fm

Yes, the Arts Show, from 6pm to 7pm on a Wednesday evening. It's great to have that level of engagement with people. You're aware of all these great things going on - then it allows you to consolidate it and hand it out to people. It's a privilege too - in the way being in the bookshop and engaging with people who have huge enthusiasms is. You get to talk to people about the book they've spent two years writing or the play that has been their obsession for years and they're now at last getting it staged. Also, radio is such an immediate medium and is one of the old technologies that is prospering in the digital world.

Do you make sacrifices for your work?

I regard myself as a gregarious introvert. I do like to get out, I do like to meet people, but at the same time I do like to have a little bit of my own space, which I probably don't give enough to myself. I can spend too much time in the public realm, just being out with people whether it's at the theatre or music gigs or whatever. That might be the only sacrifice. Some people might find the notion highly laughable that I make sacrifices for my work and for my cultural life, because I enjoy it so much.

What drives you?

I think it's just the level of interest. It's a passionate interest in what people are doing. I would probably describe myself as arty as opposed to artistic, so I'd be more appreciative of the work than yearning to produce something myself. That appreciation of what people do and curiosity about how they do it - that drives a lot of it.

Who or what has been your greatest influence?

I would say probably my parents - Mr and Mrs Browne. I grew up in a grocery shop in Ennistymon in Co. Clare. My mother was really good at dealing with people and the difficulties of the retail world. She'd never get bogged down with any of it; she'd just give people what they wanted and deal with it in her own charming way. My father was a big reader and he had a broad interest in culture. If he ever got the opportunity to go to London, he'd come back and talk about it for six months, where he had been, what he had seen. He was a Beethoven fanatic. He had a strong social conscience as well, and was very much involved in organisations that looked after people who were struggling.

What's your favourite cultural city or place in the world?

There's so many; I'd find it difficult to mark one out. Istanbul is one of my favourite cities that I have visited. It's an incredibly exotic place - you're just removed to somewhere else entirely. Places like Prague and Krakow where there's a deep, old European culture which you just get reminded of from time to time. It's important to go to places like that for a couple of days. When you're in Ireland, you're so wrapped up in an Irish world view and then you go to Europe and again are reminded that they have this continuous culture that's been going on for thousands of years. That's so seductive.

What impact do you see culture having on Galway?

Lots of people live here because of the rich cultural life of Galway. It's a very easy sell. I meet the people who work in the pharmaceutical companies in the city and they go, ‘This is a great place to live'. The knock-on effects are huge. It has a more important impact than any other single thing you can think of. It's more important than religion and as important as education. In 1963, there were 13,000 people living in Galway, and it was a kind of backwater full of people from Galway. Now you struggle to meet Galway people because there's such an influx of people who have been flooding in from all corners of Ireland, Europe and the world.

What's your vision for Galway as a cultural utopia?

I think that the whole culture that has grown up in Galway since the 1970s has done a huge amount for the city, but the whole idea of the” artist” is still hugely underrated. We don't have enough respect for the artist. If we could find some way of putting the artist at the centre of things, of saying; ‘This is important, we know you do a huge amount of work that we can't really commodify but we know it's there and we're going to reward you'. I was in Krakow recently and went to the Museum of Contemporary Art, and you do have the idea that the artist is actually celebrated in other countries in a way that doesn't happen here. In Eastern Europe, artists were celebrated because in the Communist era, they really put themselves on the line by being artists, the artistic life was both very brave and very dangerous. That's just one of the reasons that they receive the recognition in society that they deserve. It would be great if something like that is represented here. I know some artists do receive recognition because they're successful enough, but they're very much the minority and that has often more to do with money than real respect . They're not the people on the ground - the troops on the ground will continue to struggle, no matter what they deliver. We need to address this difficulty if we want our cultural life to continue to thrive into the future.

- Ruby Wallis - Previous

- Next - Fergal McGrath