Luke Morgan – Filmmaker and writer

Luke Morgan is a young Galway filmmaker whose short film made it to Cannes last May. He’s also the co-founder of The Theatre Room, a novelist and a poet.

More from...

Tell us a bit about your background...

I was born in Dublin, but I was raised in Galway - so I'm a Galwegian through and through. I went to school in St Endas - a brilliant school - and I studied film and documentary in GMIT. So now I've graduated from that and I'm a full time artist working in the creative industry.

So you went straight from school into GMIT to do the film and documentary course?

Yes, I went straight into the course. I was set on doing the creative writing course in NUIG, but at the last minute, decided to pull all my stops and just go for the more practical GMIT course. That surprised a few people, but it's one of the best decisions I've ever made. I loved the practical approach of the course, the expertise of the lecturers, how friendly the whole thing was. It was quite an intimate environment in which to learn; there was only 40 people in the class, so we knew them on a first name basis straight away. The classes evolved around discussion and debate, which I think is the best way to learn again. We'd talk about something as a group as opposed to a didactic cattle-herding kind of education system whereby one person, usually a jaded old professor, stands at the top of a lecture hall in front of 500 students and says this is that and this is that. Whereas the lectures in GMIT were always, 'Well, is this that?' and we were like, 'Yay or nay'. There used to be great arguments in the class. So I've flourished now, it's focused me and I'm pursuing a career in scriptwriting and film directing.

What have you been doing since you left?

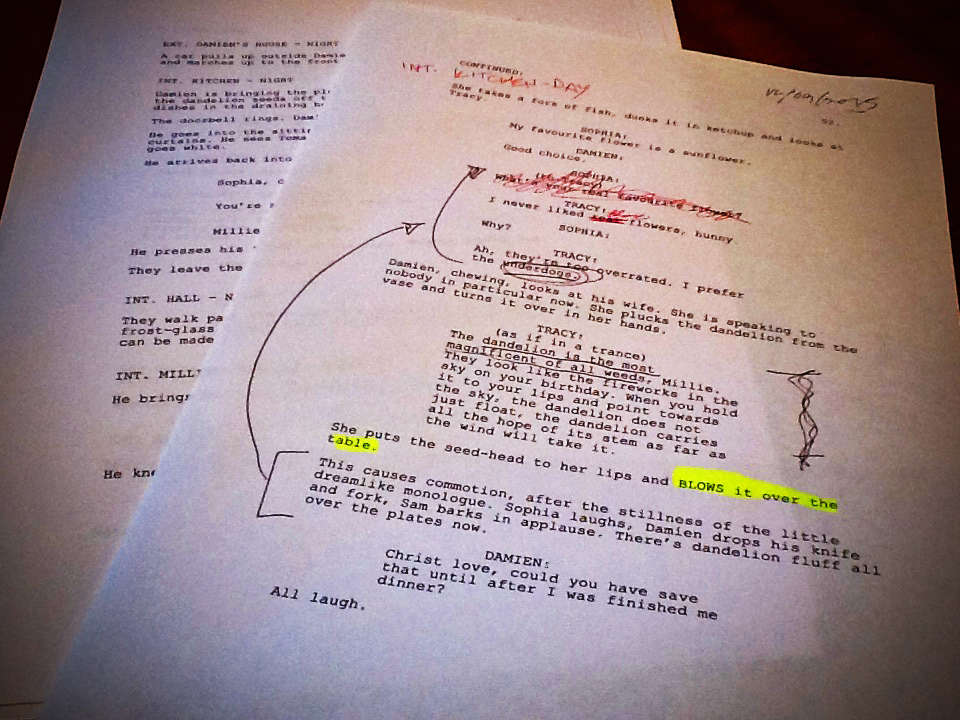

I've a few feature length screenplays in development; one of them is a children's animation and one of them is a live action. I'm actually developing a novel, 'Grain' at the moment, which is hopefully going to be taken by a publisher. I've got a poetry collection being published out in the Spring, but right at the moment, I'm making a short film called 'Heads or Tails'. We've no money, but that's often the best way to do it because there's a buzz among the cast and crew to just go, 'Let's make something'. It's starring two very talented actresses who have been part of the Theatre Room over the past year - Grainne White and Claire Aherne.

How do you find the transition of going from writing fiction to screenwriting to poetry?

Poetry is what I started out with as a kid. I had no TV until I was 13, so instead of watching TV or playing video games, myself and my brother had to entertain ourselves by other means. My brother is about two years younger than me - we're very close in age and as friends. So I started writing poetry first. Back then, when you'd say poetry to a kid, the first thing the kid thinks of is, 'OK, it's got to have four lines in each stanza, and at the end of each line, there's got to be a word that rhymes' - but that was really unattractive to me. There was no part of me that said, 'I'm going to sit down now and right a poem' - it just kind of happened. I just started writing passages that I wouldn't have described as poetry, but more and more as it went on it became clear to me that that's what I was doing. A teacher in secondary school, Gerry Hanberry, a renowned poet, took me under his wing and really encouraged me to keep doing that. But then the jump from poetry to screenwriting isn't as big as people would think. A lot of people think that a novel lends itself more to a screenplay or a stage play lends itself more to screenplay, but in terms of the sub-groups within writing, I think poetry is probably the closest. When I say that to people, a lot of them are like, 'What are you talking about?', because when you think of a movie script, you don't exactly think of Seamus Heaney, but you've got to be so efficient with the language in a poem. And it's so visually-based - it's completely based on image. You've got to get across a very complex theme or scenario just entirely with an image and that's what screenwriting is and that's what film does best - it tells stories with pictures. That's something I discovered when I leapfrogged into the BA in Film and Documentary course - I discovered that screenwriting is so similar to poetry, so I felt that I had something that not everybody else had because it's not the obvious transition.

Have you ever had any formal writing training?

I've taken various workshops over the years, but the only way to learn how to write is reading. The best piece of advice that I was given in terms of writing was 'read and hour, write and hour'. It's so true because by reading, you learn. If you enjoy it yourself, or if you don't like something, it's equally as important because the cogs in your brain are asking the question, 'Why don't I like this?'. There are a lot of writers that don't read because they don't want their work to be influenced by anybody, so they won't touch a book; I think that's ridiculous. The only way to learn is to be inspired. What drives me is when I read something or see something and I'm just completely inspired by it - it just reminds me what it's all about and that is moving somebody. You can talk about the latest camera model or you can talk about the best actors on the red carpet in Cannes, but what it's about is dazzling people with spectacle and distracting them so you can get straight to their heart, because it's shovel work at the end of the day. When I get up and I write and write my 2000 words every morning, most of the time it's not like I'm sitting down and it's spilling out of me - it's shovel work, it's getting your bum on the seat and forcing yourself to work.

Do you find it difficult, getting over that hump and seeing it through to the other side?

That's the difficult thing. Where I used to work, you have a supervisor over your shoulder whip cracking, saying you have to have a certain amount done by this time. I don't have that because I'm a freelance writer; I don't have anybody over my shoulder telling me I have to have this done by this time, so you have to make my own deadlines and you have to adhere to those deadlines, not because you're trying to please the boss because the boss is yourself, but you believe it needs to be done. And in order to reinforce that you believe that it needs to be done, that comes from reading other novels or watching other pieces of film or listening to a piece of music where you're like - 'My God, I just want to create magic like that - even half the magic that has. So it's constantly nudging. You allow yourself to access other words, you're constantly reminding yourself of what it's about and what's important. I tend to stray away from writing courses and stuff like that because often they make out that there's rules and there are no rules. I mean, William Goldberg says that on his grave, he's going to have the words - 'Nobody knows anything' and that's true. Sometimes a film comes along that everybody says 'No, it's not going to work', and it just works and it just proves that there are no rules - nobody knows anything, nobody knows what works. Following 'rules' or dos and don'ts, you're using the right side of your brain and you're stopping and starting. You can't be in editor mode while you're trying to create because if you're constantly correcting yourself, it's like an engine stopping and starting.

Your short movie, 'Pockets' was accepted to the Cannes Film Festival Short Corner last May. How did that come about?

I just lobbed out a film and got lucky. I went over and that was a great experience in itself. It was very educational. When you say Cannes to someone they think of glamour and they think, of the beauty of cinema, but really Cannes is like a fashion event on the surface but under the surface, it's a business market; it's one of the biggest business markets in the world. The Palais, which is like the main building where everything happens in Cannes has all the stalls where every single country in the world is represented and each country is selling x amount of films. The floor is about as big as four football pitches and you're just walking around and looking at all the posters of film that all these countries have made and now they're trying to sell them. It really hammered home the fact that film is a product in a lot of ways, just like toothpaste is a product and once you've got a film made, which is an incredible feat in itself, it's only the beginning of the journey. In order for it to find an audience, it's got to have a poster and it catches people's eyes, you've got to be able to tell from the font of the title what kind of movie it is. So it was a bit of a reality check for me because I've always been the kid who's always been enamoured by the magic of film and here I was just going, 'No, it's actually all about selling'. But I've still managed to remain that little kid who looks up at those big images and is dazzled.

Brilliant to have achieved at such an early stage in your career…

The main reason it was so good is that it gave me the opportunity to go and to meet people that I otherwise wouldn't have gotten the opportunity to meet - just shake the rights hands, smile when I was told to smile. And out of that, I met people in Cannes that I've got stuff in development with at the moment.

How did the Theatre Room start?

I don't have a background in theatre at all. I've always loved theatre, I love going to the theatre. Myself and my friend Seosamh Duffy were sitting down one day and we were thinking that we'd love to do some theatre. The theatre scene in Galway is quite cliquey and of course we didn't have any official training - we couldn't talk the talk. So we thought, right, let's just start something and not pretend that we know what we're doing - take amateurs, take all ages and let's have it free so nobody makes money out of this. We didn't have anywhere to put it on - all the venues were too expensive so we said, 'Fuck it, we'll do it in the living room'. So it started in the living room of my rented flat in Galway.

So last January, we had our first Theatre Room. I just loved the idea that it's free to the public, people come, they sit down on sofas and kitchen chairs, they drink tea and they just watch good writing and good acting happen before them. Yeah, we're in a living room but we're also under the ocean or we're in the middle of the woods at night or we're in a spaceship. I love that idea. And there's no props - the only props they can use are the things that are immediately available to them in the room. So many people embraced it straight away - as soon as we had the first Theatre Room, we thought, 'We've got something here - we're onto something. We don't know what it is - it's impossible to turn this into a commodity, because we're amateur writers, we're amateur actors, we're amateur directors, but there's an energy'. Anybody who's been to a Theatre Room has come up to me and said there's an energy that's impossible to ignore. There's people who have never acted before in front of an audience but they always thought they'd love to act and they've been in a theatre room play and they've come down off the 'stage', everybody claps and there is that sense of personal achievement. Then of course as it got bigger and bigger and we had to move out of the living room because there were too many people coming - my kitchen could only fit 30 people.

So the Theatre Room got bigger, moved into the Bank of Ireland Theatre for a month - we did it in UCHG - did a show there for the kids at Christmas, we got the Druid emerging artist residency and we were in the Mick Lally Theatre. So we had formed this kind of family - this troupe of travelling actors, bringing all these people into these venues that they did not see themselves performing in. All of a sudden, they're in the Mick Lally Theatre. It's been really surreal and also amazing - there's a real sense of community, a sense of family, like there's people of all ages in the Theatre Room but it's mostly young so there's a real sense of something happening. It's almost like a revolution - I know it sounds like I'm exaggerating, but it's really exciting.

How does the Theatre Room work?

It's a completely collaborative thing, so after each play, which happens once a month, the structure involves a writer getting up and pitching his idea of the audience. Anybody in the room who is interested in directing the piece can put their hand up to direct it. The directors then have to pitch themselves to the writer, so the writer picks the director, the script is auctioned off. So let's say we have six scripts from six different directors, the room is then split into six and all the actors and actresses who were in the audience can then go from table to table auditioning for whatever plays they want to be in. So those are the plays that are going to be performed at next month's theatre room. So it's like, 'Ok guys, go away, we'll see you in four weeks for the plays' and then we have the plays, we have a break then we have a pitching session for the next round of plays so it kind of sustains itself that way. It's very much like Little Cinema; there's a similar vibe. We plan to collaborate with the Little Cinema guys on some exciting projects in the future as well, because we're big fans of theirs and they're big fans of ours.

What's a typical day?

I'm an early riser so in the morning, I get up and work on the novel. I'm a bit scattered having just woken up and that's the perfect headspace to be in when you're writing a novel, because you can just splurge. I get my 2,000 words out of the way and then I take a break for breakfast and then I might sit down and do some screenwriting. Screenwriting is actually a lot more mechanical - every single line in screenwriting and every single scene has to have a passport. When you jab your finger at it, it has to have a reason for being there. It's like building blocks; you take it apart and move it around. It's kind of using a different side of my brain.

I might take lunch, have meetings with crew. For instance, I'm in a process of working out a short film at the moment - it's like setting up a small business, making a film. So I have to meet the production designer or I have to meet the producers or I have to meet the cinematographer and do a camera test or something like that. There's about 16 different people on the crew and cast, so it's a people's sport - you're just constantly touching base with different people. Film is just amazing because it is a collaboration of all these different art forms. It's about being the person to balance that and go from department to department, You have to be a leader I suppose.

And that's you?

That's me. That's my job as a director anyway, whether I do a good job or not. But generally I think I would describe myself as a leader. I'm the oldest child, so it follows.

Where do you want to go with what you're doing? What's the plan?

The plan is to keep doing it and survive with my head above water for as long as possible. The arts has a reputation for being very difficult to live off and people have said that to me all my life. I'd say, 'I want to be a writer when I grow up and they say, 'Oh, that's cute, but what do you actually want to do? What's your real job going to be? So I've always had this mentality of, I'm going to prove that I can make a living doing what I love. So that's my plan - to be able to keep doing what I love doing and hopefully motivate others to see that they too can do the same, as opposed to slugging it out in a 9 to 5 office job because they didn't get into that dance school.

Do you think the community in Galway is supportive of that?

Everyone's got peers and of course, when I see Galway, I see a bunch of artists, but that might not be the same to the guy who works in retail, or the girl who works in an insurance company. The people I work with day-in day-out, the people who come to the Theatre Room, and the people who I work with on my films are all chasing something similar, so there's a good momentum building I think, particularly among the young people in Galway - it's good to be wrapped in that energy. So I think it's very supportive. And the Galway 2020 guys are great. I was invited to be on the presentation panel to represent young artists in Galway. They're a great team - very charismatic. I was drafted in for a week and did the best I could. I was very much riding on the momentum that had been built up.

What drives you?

Probably hearing my brother Jake's music reminds me that if I don't get up off my arse and do something, I'm going to be the Morgan brother that everybody forgot about. He's a composer and he just makes the most incredible music.

Who were your major influencers/ mentors along the way?

Myself and my brother grew up in a matriarchy, so all my mentors have been women - my granny Peggy, my mom. Then going through school, I've had great teachers; Leisha Lyons, my sixth class teacher in primary school in St Ann's National School in Roscahill and Celine Curtin, who heads the film and documentary course in GMIT. And my girlfriend Annie McMahon of course. I'm the product of a matriarchy.

What's the film scene like in Galway from your perspective at the moment?

It's thriving. Apart from Dublin, it's the biggest in Ireland, and of course Galway is the Unesco City of Film now, which is fantastic that we've got that recognition. The amount of people that are employed in the film industry in Galway is far bigger than most people even realise. I hardly realised it myself until I went to GMIT. You've got Telegael, Beochan, and you've got TG4, and Ros na Rún. It's amazing, and some really great stuff is being shot here. The Galway Film Centre puts on an excellent seminar every year, which just ended a couple of weeks ago and they had Asif Kapadia, the guy who directed Amy and Senna - two of the highest grossing documentaries in the world. In the past, they've had Vince Gilligan. It's amazing to be living in a place where this hum of activity is all happening all around you. It's so encouraging for a young filmmaker like myself to know that there are these people dotted in my immediate environment who are kind of cheering you on.

So you're happy to stay here?

There's a lot to be said for the contentment and way of life of living in Galway. It's only really when I go abroad that I realise, 'God, I have everything that I need here'. It's like this little catacosm of a perfect bundle - it's not too big, it's not too small, it's friendly. It rains a lot yeah, but when the sun shines in Galway, it's the best place to be in the world. Galway has, in the past, got a bit of a bad rep in the past for being 'the graveyard of ambition', but I don't see that. All I see is that I walk outside my door and I walk 200 metres to get milk in the morning and I pass two people on stilts, a paper maché fox and a busker single the 'Auld Triangle'. Where else in the world is that going to happen? You can't but just sigh and say, 'Oh Galway'. It's a brand at this stage.

What's your vision for Galway?

I think Galway is great; obviously, there's the easy answer to say if we had more money, a lot more things could be done. Being part of the 2020 team, I had read the bid book and I was reading all the projects that we would do if we were to get the Capital of Culture and a lot of those things just really excited me because of the scope and size of the projects. But I'd love Galway to be a place where artists, writers, musicians, from all over the world came to retreat and be inspired, but it kind of is that already. I suppose if you were to ask me this time last year, I would have said I'd love Galway to be a place where you could walk down the street and walk into someone's living room and there's a play - but that's why we got up off our arses and did the Theatre Room.

- Louise Spokes - Previous

- Next - JP McMahon