Joe Boske – Visual Artist

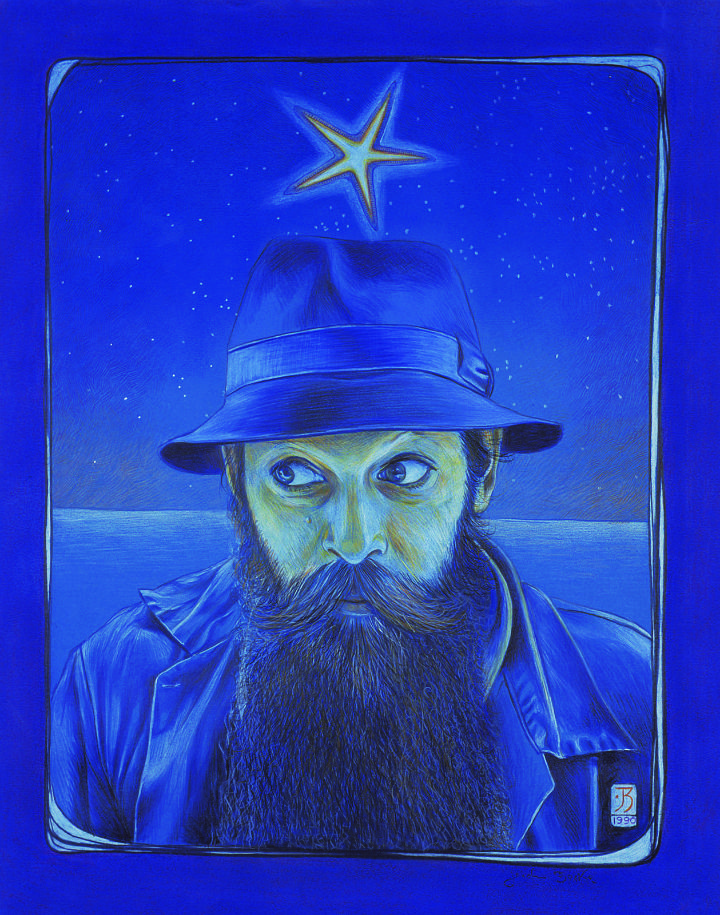

Artist Joe Boske, with a love of surrealism and 'daftness', has produced some of the most iconic artwork Galway has ever seen.

More from...

- Joe Boske - The Works published by Artisan House

Tell us about yourself...

I was born in Germany in a place called Wolfsburg, the Detroit of Lower Saxony. I wanted to study art when I was quite young. Here, people go to primary school, then secondary school when they're about 12. The system in Germany was that, if you showed any academic promise, your teachers and your parents would collude to either send you off to the 'big house', the Gymnasium, which would prepare you for a place in university. If you're only a semi dunce, you go to secondary school. I was a semi dunce, being not so academically bright, but I was quite good at drawing. I left secondary school when I was 16. You cannot go on to study in Germany until you're 18, unless you're exceptionally gifted. I applied but I didn't qualify, so my parents decided I should do an apprenticeship in a field that was related to graphics. In those days, it was compositing in a printers. I did that for a year or two. As an apprentice, you're first and foremost the feckin' gofer - that means, 'Bring away the lotto tickets for the girls in the bookbinders and don't get caught by your foreman'. Or 'Buy beer for the printers and don't get caught by the foreman and come back here by…'all that kind of stuff. I did about a year and a half of that and I got a little disillusioned, you could say. I was just 18 and the minute I got my passport - bye bye, out the door and gone. I was bullin' to go. So I went away to Ireland and I stayed.

Why Ireland?

When you're young, you're interested in everything. My parents brought us to Denmark and Sweden, the north of Germany and France, but I had never been to Ireland. I saw a couple of films about Ireland and it appealed to me, especially the music. I listened to a lot of Scottish and Irish music on the radio, which I had never heard before previously. I got very interested in that. Then I did a little research. I went to the local library - there were about three and a half books on Ireland, so I read them all and I said 'I definitely want to go to this place'. When I was about 17, I was a year into my apprenticeship and I said, 'This stinks', so I put a few bob aside. As an apprentice, you get paid damn all, and then one day, I did not arrive at work because I had the ticket booked and I was off. My parents were upset, of course; why wouldn't they be? After a few days, they got a postcard saying; 'I'm in Ireland. I'm staying. Bye bye'. So that was it. That was 1969, and after that, I travelled around a bit. I ended up in Cork at the end of the year, and I went to an exhibition of student work and I thought, 'Jeez, that's not terribly brilliant', but I started talking to the curator of the gallery and he said, 'There's an art college here in Cork. I know everyone there and I'll introduce you. So I got introduced to the principal and then he brought me around the first class and second class and in the first class they were drawing triangles and squares and I thought, 'This isn't for me'. So I told a bit of a fib and said I studied for a couple of terms in Germany - telling lies. I enrolled in second year and it cost 7 pounds for the whole year in those days. I had worked in Wales on a farm and a building site for a month or two, so I had the money. So I enrolled in the Crawford School of Art and was there for the year. Then I applied to the art college in Brunswick, which is near my hometown and got accepted. I moved there in 1970 and studied for another two years. In the interim, I was a young buck and I got married to an Irish woman; that didn't last too long. We moved over to Germany, but every other few months we were back in Ireland. So I graduated there, spent some time in London and then moved back to Ireland in 1972, and I've been here since.

You've had two books of poems published, do you still write poetry?

I do, but I haven't published any of that stuff. There's a long rambling lyrical streak in me and then I have the bon mot - three lines. Bang! Flash fiction, finished. That's another aspect of what I do and I have to prune that down, dickie it up, read through it and edit it. Eventually I will. As of late, I did a book - in it there's a mixum gatherum of serious art and then there's cartoons and commercial stuff, but the next book will be complete madness. Once I have that out of my system, I'll get serious again. That's if my eyesight doesn't fail and I don't die of diabetes!

How does that work for you - swaying between the 'mad streak' and the more focussed side?

The serious stuff is counterbalanced by daftness; it has to be. Otherwise, you become this kind of in-grown toenail teuton. You get the very serious types, the deep philosophical ones. Yowl. God forbid. There's an element of that there, of course, but the overall view is slightly more jovial.

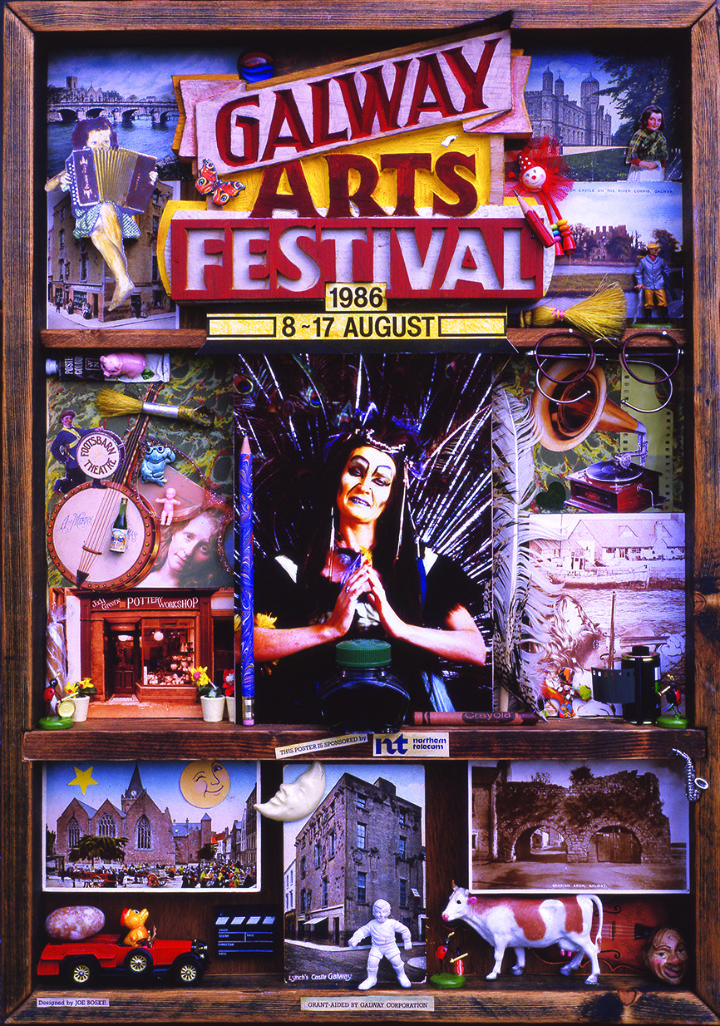

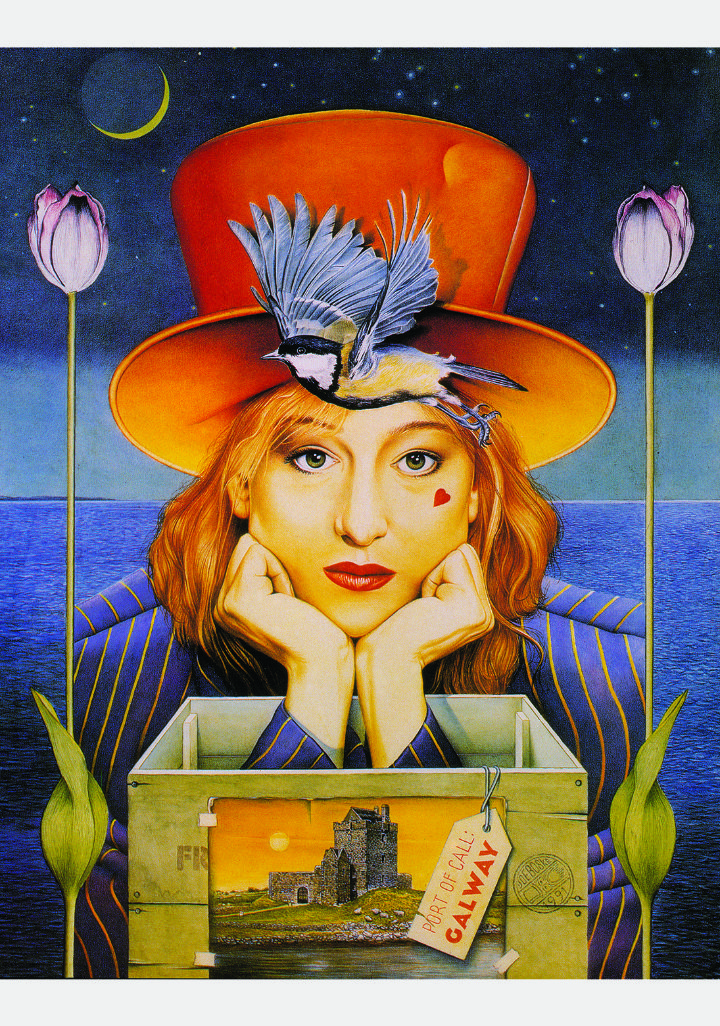

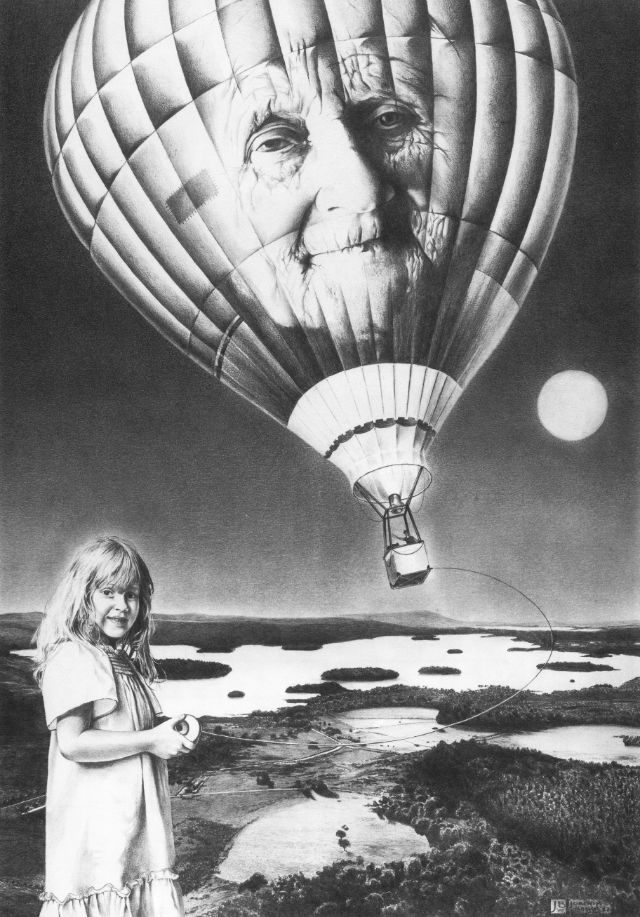

You're well known for your iconic Arts Festival posters. How did they come about?

I split up with my wife sometime in the mid 70s, and I was living in Dublin for a while. In those days, In Dublin Magazine had started. John S Doyle was the editor, and the likes of Fintan O'Toole and a lot of writers that contributed in those days - starting off as journalists with In Dublin, contributing different articles. Basically, the first ones were listings magazines and then it fleshed out over the years and it became a lovely little magazine about topical issues and political ones. Then John sold the franchise and it became a rag; they put ads in about massage parlours and all that sort of shit and then it died a death. But before that happened, there was a guy who was working on that paper who said, 'Wouldn't it be a good idea to do something similar in the West of Ireland, calling it 'In the West' - that was 1977. He had moved over with his family to Furbo at the time. So I started working on it. As a graphic artist, I did everything from designing it to doing the cartoons and lots of other stuff. I did that for a couple of issues. We were paid damn all - sandwiches and sleeping on couches, and a couple of pints and all that nonsense. I mean, I was enthusiastic, but it became less so for me because there was no editorial direction, so I got disheartened. Plus, you can't sustain yourself on sleeping on couches and drinking pints. During that time though, I had forged links with various printers, so I got jobs on a freelance basis from a few printers, and I left the magazine. It died after a couple of issues. Around that time, the Galway Arts Festival started with Ollie Jennings and all them. I mucked in. First of all, I did poetry readings. Ted Turton did one or two posters, then Ollie discovered that I was an artist and I did one or two. Then in 1984, it all went full colour. Full colour in those days was 'Hello!' There's a poster of mine in Neachtains from '84 - it was a big poster, and no printer in Galway could do full colour that size then, so it was franchised out to Turners in Longford. I did a few more of those. In the 80s, I moved over to London because I got a job there. When I came back in the late 80s, early 90s, I moved way out to Connemara. I had enough of tubes and the sound of traffic, and so I moved to the West and I've been pottering around that region for the past 25 years.

There's a real sense of magic in your Arts Festival posters. Where did your ideas come from?

Well, I'm kind of daft. The danger with most people that commissioned anything in those days was the linear thinking. It would kill anyone. You saw it with advertising. When I came back from London, advertising in Ireland was very straightforward and boring and yawn. In London and other places, they did something whacky, and it's the wacky stuff that sold. Now we do wacky stuff in Ireland, but in those days, it wasn't done. So back then, I'd produce a drawing, something completely daft, and I'd say, 'trust me'. And it worked. I kind of half knew that, and it did. But I do change; I don't plough a furrow - I diversify here and there. But then when a thing is successful and it works, they want you to do this thing forever more, which is another way of inverted linear thinking, so I stopped doing them. And also to give other people a break.

What work are you most proud of?

The stuff I haven't done yet.

How do you feel about the work you've done?

I like some of them. Some of them I feel are the true me, but there's a load of commercial stuff in it, because I've done lots of that over the years. The rent has to be paid. Some of it is a compromise - a lot of it is compromise, but you arrange yourself with whoever commissions you to do something and hopefully, you can do whatever they have in their mind - you want do them justice. Hopefully, there's a few years left in me and the eyesight is good enough that I can.

What are you most interested in working on next?

There's the music, which I haven't done much of recently. I had an album out quite some years back. So the boys would have to rehearse, the poor bastards. 20 years ago I composed a few tunes - I had an idea for an exhibition that you walk into and you hear music that can transport you while looking at the pictures.

Do you play the music yourself?

I'm not a very good musician - it's like pulling teeth with me. It's in there, but it's very hard to come out. I play a bit of guitar, and a bit of bouzouki and a bit of whistle, but I'm not a practicing musician. I know what I want, so I write the music but I don't write notes. I've no skills in that regard, so I'm a tedious musician.

So how do you direct the musicians?

Well, they're friends of mine over the years. I tell them and they half know - all of them are proficient musicians. So it worked out very well for this project. Initially, I didn't want to do an album or a CD but having all this stuff recorded, which took about two years, somebody said, 'Why don't you put it out on a disk?' so I said, 'Yeah, why don't I?' And that was 19 years ago.

Would like to compose more music?

Yes, but I haven't done much. I broke my arm last year, and I haven't taken up the bouzouki since. It's there. In the interim, I said I'd do the writing. I'm never idle. I'm always dipping into honey pots here and there.

What are you working on right now?

This book, which is kind of daft writing and poetry and mad stuff and cartoons mostly, so that will be the next one out. You have been warned!

Who's influenced you in your work along the way?

I don't do hero worship, but I have some people whose work I appreciate, especially some of the early surrealists. When you're young and you can say, 'This is whacky shit, no one does this and nobody in my immediate surroundings even knows about this' and you say. 'I like this; it speaks to me'. Then 20 years later, you think, 'OK, a bit thick maybe', but you're receptive. I was never terribly impressionable but I was receptive to things that were slightly off the beaten track.

What about now - anyone who's work you admire?

There are some very good cartoonists whom I like. Tom Mathews is an old mate of mine; he's just daft. I have very good woman friends of mine who hate puns - the lowest form of wit and all that, but this is my forte. I love it. It's just one aspect. Glen Baxter - just whacky. Gary Larson, an American cartoonist - brilliant.

Describe yourself...

I like whacky stuff. My mother was the same, just circumstantial kind of lunacy. Like overhearing things, just chance encounters and chance situations, where you go, 'What the hell is that'. Because the world is daft, it is! Most people have a funny bone that is not quite on the straight and narrow and it's just to nurture it a bit and bring it out to the fore - lend a bit of credence to it.

What do you like about that side of life?

Every aspect. I don't go around being wacky; I'm not a performer. I'm fairly rooted and you have to be. You have to be fairly centred, but I love off-shoot stuff - daft things you read and think, 'The human is an interesting species - what have they done now?'

How would you like to see for Galway going forward?

When I came to Galway, there was very little. There was a university but there were about 8,000 students there, and now, between the various colleges there's tens of thousands. It's a youthful town and there's lots of things happening. We still don't have a proper feckin' gallery though, apart from the Arts Centre which is an awful shame. To think though that it all came from someone saying, 'I think we'll have a little festival here' 30 or 40 years ago. A buzz was created then. All of that positive development has happened in the space of a few decades. Now the arts is worth millions to the town; it now has a cultural whitewash - that wasn't the way 40 years ago. So a few people were instrumental in paving the way for that to happen - Garry Hynes, Ollie Jennings et al.

I think worthwhile efforts in any field, from publishing to theatre to the visual arts to music, anything to do with culture in the broader sphere, need to be properly financed. Because any small theatre company that puts on a play even the smallest of plays, ten grand is piss-money. To do a worthwhile production where people have the enthusiasm and the skill and the expertise and the training, they need to get the proper financial help they deserve to make this it all a reality and enjoyable for all.

Updated: 10th April, 2016 with requested revisions.

- Louise Manifold - Previous

- Next - Mark Campbell