Noeline Kavanagh – Artistic Director of Macnas.

Noeline is the creative brain behind the spectacle and street performance company, Macnas.

More from...

Can you tell us a bit about your background? How you became involved in the arts?

I grew up in Renmore. At the time it was a great environment because there were great kids in the estate. There were open fields and there was Ballyloughane Beach. You played rounders down in Renmore Park, British Bulldog up in Renmore field, and there were always foreign students because people needed to earn an income, so we had all this amazing mix of teenagers. It was all very 80s - get out in the street, play till 11-o'clock at night, draw chalk on the road, rounders, scotch, tennis, hurling and sliotars - all the usual, but I loved it. I remained in Renmore until I was 17 and then I did my Leaving Cert and I skirted off to UCC because I suppose I had a little adventure in me and I wanted to do college outside my home town. Then after a year I dropped out because I discovered Dramat, the college drama society. It was a seminal moment really, because I remember meeting John Crowley who's now this amazingly successful and brilliant artistic director and I remember he was a philosophy student, an English student and he was in third year or doing an MA or something and he seemed amazingly cool to me at the time. I remember him saying, 'Don't be arsed doing the degree, if this is what you're into, don't hang around'. So I took that advice and my parents weren't exactly delighted.

So I came back to Galway, joined Galway Youth Theatre and I joined Flying Pig Comedy Troupe, which was run out of the old King's Head… and I loved it. Being in the Flying Pigs was an amazing opportunity really. There was a group of us - five or six of us who came together to write all these comedy lunch time performances that ran for two years. And it was a great training in ensemble, in creative thinking, in performance energy, and making great friends. I was mad about it. And then also combining that with GYT. At the time there was a lot of older young people involved in youth theatre. They were 19, 20, 21, 22. It was a kind of breeding ground for that tribe to evolve. Macnas was also always a constant in my life because I was very attracted to the energy and the style of work it presented. I related that directly back to Els Comediants coming to Galway when I was ten and seeing that on the street; a kid from Renmore watching naked Spanish people come down the town with a dragon and breathing fire. I remember standing on the street in the lashing rain and there was this pandemonium; you could hear these drums, but you couldn't see anything. You could hear this roaring and you could smell the smoke. And then, out of nowhere, these masked crazy demons and devils dancing with bare arses were weaving their way down the street. I just remember this dragon coming right up to my face; I looking at the dragon and it looking at me and it was like, "Ok, like, I get it. I hear ya". I remember sitting in the back of the car on the way home and saying to mum and dad, 'What else would you want to do with your life? Isn't that just brilliant'.

So after finishing your drama studies at Trinity, you returned to Galway to direct the Macnas Parade?

It was 1998 when I first directed the Macnas Parade. I was the first woman and I was the youngest at 23. It was amazing. It was super challenging also because it was a very political time where there was a lot of building happening around Galway, and there was a lot of resistance to these new buildings going up in traditional spaces. I got Ray McBride to play the King of the Fools. We did a very satirical parade because I think I was at that really vibrant age, where I was like 'Challenge the system - let's go crazy'. It was one of the largest parades ever - there were 500 community participants in it.

What then?

I thought it was a good time to leave Macnas and go and expose myself to different art forms both in Ireland and abroad. So I started work as an artist in residence at Fatima Mansions and ended up living in the flats for six months and being part of the whole regeneration programme. It was a prime site in Dublin where they wanted to level the flats and use it for commercial property, so I was involved in a whole process over nearly five years in closing off a cycle with the residents who wanted to hold onto the land and redesign their homes on their site. So that was an amazing time. At the same time, I was an Assistant Director to Rough Magic, so I was working with heroin addicts and kids in a housing estate and then I would go into rehearsal space with actors wearing posh frocks, so it was a real hybrid of two worlds.

I then got offered the Associate Directorship at the Abbey, where I was afforded this opportunity to work there for a year in association with different directors. But it just wasn't for me; it was a little bit too structured to suit my disposition. Instead, I went down to Carlow and ran a youth theatre for a year and a half to see what it was like. At the end of that, I was making a piece of work for Tom Meskell, who's an amazing visual artist, in a manky warehouse when this guy called John Fox, from the internationally renowned company called Welfare State International, came across me in the warehouse and basically asked if I'd come to the Lake District. So I ended up going over and working with John Fox and Welfare State. I got to be the Performance Director and directed the Carnival Opera over three years. As result of that, I got to connect with the Parisian company Theatre du Soleil and did an internship with them. Macnas ended up doing a collaboration with Els Comediants in 99/00 that I ended up working on. Then separate to that, they did a collaboration with the St Patrick's Day Festival. So I got to work with the people that made that dragon that I saw when I was ten and actually, they brought the dragon over so that was an amazing symbiosis and I was co-directing that production with Els Comediants. So it was kind of like everything started to fall into place, and then we closed Welfare State in 2006 after 38 years.

I then freelanced around England and worked with companies like Walk the Plank and Liverpool Lantern Company and I did a short film for BBC, in collaboration with Tom Lloyd and Dreamtime Film, about a boy who wanted to be a magician and he lives in Blackpool. And it actually got selected to go to Cannes.

So you've been Artistic Director with Macnas since 2008. What does your work entail?

I'm a creative director as opposed to a theatre director. Macnas is a company where you're a performer, a musician, you're a chef, you're a stage manager, you're a welder, you're a costume maker. So all of our team have a massive variety of skills that is more conducive to a kind of collective way of making work. It steps outside the more traditional theatre model where you have your artistic director, you have your stage manager, your set designer. We work as an ensemble. The work I make in this company is as a result of the ensemble that I have around me. I mean, I come up with an idea but it is the creative team that basically enable and bring that vision to life. Of course you need a driver at the helm, but you also need your amazing group of engineers of imagination to basically go - ok, there's this idea - this is how we bring it to life.

Amazing for all the people who work with Macnas to have the opportunity to try different things and to develop their artistic abilities...

Absolutely and I think that's important. I think that it's constantly reinventing the formula, and it's giving more liberty and more freedom to more creative people to develop their skills, enhance their skills, and challenge their skills.

How does art and culture influence your daily life?

I think that art and culture has saved me in the sense that I found my tribe. It showed me an avenue that you can be who you want to be and that you can make a difference in the world. I think that it is in the fibre of who we are and it's informed a lot of who we are as a people. I think that it's as essential as breathing, and it doesn't have to be something that's on the stage. I think you look at any kid and you know, whether they listen to music, they see a film, if they come across a puppet, a doll, a song, a dance, a toddler discovering music - that's what culture is. It puts the shizzle in your grizzle!

Do you find you have to make sacrifices for your work?

Yeah, I do. I don't think you can do it all. And I think that people are told a lie. It particularly puts women under a lot of pressure. It's like - be a certain kind of person, be a certain kind of way, have a great career, be a great wife, be a great mother, run a company, be feminine, be masculine, be ambitious.

If you care about something, if you need to do it well, you need to sacrifice. I'm not a parent, but I have a lot of friends who are and I think it's like parenting. It's like you have to give certain things up because there's an unconditional love that is required to deliver and I think that in creating work and in running a company like Macnas, you have to put it first because it deserves it and if you put it first, it means you're going into an agreement that you believe in it and it believes in you. So there's things that I probably could have focused on more but I was like, ‘Do I want to do this, or do I want to do this?' But I think I'm coming to an age and a stage in my life where I don't see it as a sacrifice - I see it as a choice now. You know? I feel privileged and I feel humbled and I feel honoured to be making work and to be creating work that I love and it makes me healthy and it makes me happy.

I also think that as well on the other side, there are people in the company that have families, there are Macnas children. And I think that's what makes the company interesting, diverse, healthy. For a long time, I thought I should have been walking a certain road when in fact, it wasn't the road I wanted to walk - and it's not ok to say that as a woman.

“When you think about Ireland 30 or 40 years ago - there was this hive of artistic inventiveness happening on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean and you think about how that's been built up. And it hasn't even reached its potential; I feel like it could go panoramic in so many different ways.”

How would you describe yourself?

I would describe myself as someone that is sociable, that is open, that is wanting to learn, that is making mistakes, that is wanting to create and evolve and develop and move forward and make a difference. That's the kind of person that maybe I would like to be! I hope I'm somebody that listens, that tries hard. I'm somebody that believes. I suppose I'd be passionate - I'm passionate about my friends, my work, my life, my family. So, that's the kind of person I am.

What drives you?

I think love drives me, imagination drives me, friendship drive me, possibility, chance, choice, challenge.

Do you work on instinct or do you think things through?

I kind of work on instinct, and then afterwards, which I think wrecks Sharon's head (Manager of Macnas, Sharon O'Grady), I think things through. I work on instinct but it also doesn't come easily, to get to the truth. There are certain levels of instinct. You can have a nervous instinct or an apprehensive instinct. So actually, I work from truth and I think that sometimes you have to really excavate it because there are these false shadows that come up.

"Now the most exciting thing is, what are we giving the next generation? What legacy do we create now so that they can go off and develop and create a wondrous whole new tapestry that basically reduces us to nostalgia and passes us out because that's the purpose of life, is it not?"

So do you take some downtime or quiet time to help with that?

I try, I'm not very good at it and I don't know if that's the best thing for me, my family, friends and the company. But I am trying and I do things like jogging to try to turn the brain off, to let the instinct through but also to let the body relax, to work out the adrenalin. Because if the body is like that all the time, it's very difficult for that instinct to come out. So it's about trying to find those moments of time and breath, and it's about landscape and nature - taking a walk, going to Coole park for a day, going out to Diamond Hill, looking out on the Atlantic Ocean. I know that can sound really pretentious and arty farty, but I'm only talking about it as the effect of sitting in landscape, how that can really bring you back into the body and into yourself and that's how I like to relax.

Also, seeing beautiful work; there's nothing like it. Watching other people make beautiful things or hearing a great music session - those kinds of things. When you watch other people make beautiful things, or things that affect you or impact upon you, it allows you to look at the world and go, ‘God'. When you were asking me what does art and culture do - it does that. It shifts your perspective, it allows you to breathe, it allows you to cry, it allows you to connect. It allows you to be inspired, it forces you to be jealous, it makes you angry - it brings up all of those things in the same way a storm does or a swim does. Or being out in the pissing rain in Connemara and you're going, ‘What the fuck am I doing here?' and you've got these big mountains going, ‘What the fuck do you think I'm doing here?'. So there's a lot of holy holiness to it. And it seduces you, it brings you back to the basics of - I'm human, and so is everyone else, and we are just on this earth to do these things.

Who/what is your greatest influence?

I think Macnas has been one of my greatest influences. I have to utterly own that - this company has afforded me an opportunity to view life through a different lens, and all from my hometown. And all of the artists that were creating work when I started as a 17-year-old, they're all my greatest influences because they allowed me to think beyond the obvious. Also, seeing the shows in Galway as a child - the Galway Arts Festival, people like Trish Ford bringing Royal De Luxe to the city when you're 14 years of age and you're sitting in the Cathedral carpark with your dad and you're going, 'Who the fuck thought we'd be watching this?' Padraic Breathnach and Ollie Jennings bringing something like Els Comediants to the town - like bringing Spain to Galway. That's vision. And the knock-on effect for that is that it inspired the now 40-year-old generation to exist. Now the most exciting thing is, what are we giving the next generation? What legacy do we create now so that they can go off and develop and create a wondrous whole new tapestry that basically reduces us to nostalgia and passes us out because that's the purpose of life, is it not?

"I think that culture has absolutely given Galway an identity that has been recognised across the world as this innovative, exciting, amazing, beautiful interesting city that is just populating itself with energy, diversity, newness and creativity."

Any new projects in the pipeline?

At the moment, we've just got a new street show that's going out to Valentia Isle Festival in Kerry. It's also going to the Clifden Arts Festival, Westport Arts Festival and it's just come back from Lithuania. We're also now developing another magnificent Macnas parade that will whore and tour its way through the streets of Galway on Halloween night, so all of Galway please come out because we love you and support us. And then we're going the very next day to Dublin to do the Bram Stoker Festival, which is taking all of the work that we've premiered and made in our hometown, and presenting it as a spectacle show in Dublin. Then we're going to be working on a very exciting work-in-progress piece that we're going to be doing in our warehouse - a new mid-scale spectacle theatre show that we won't have the money to do for the next 500 years but who cares? Let's start and see where it gets to. And then next year we're going to London and the South By Southwest Festival in Texas where we're doing a spectacle show as part of the 2016 commemoration of Irish artists abroad and we're also going to be for the first time ever in the London Irish Parade going through Trafalgar Square with Crom, the God of Fertility and Destruction, representing spectacle art for our genre in this country abroad.

So where do the ideas for the stories behind the parades come from?

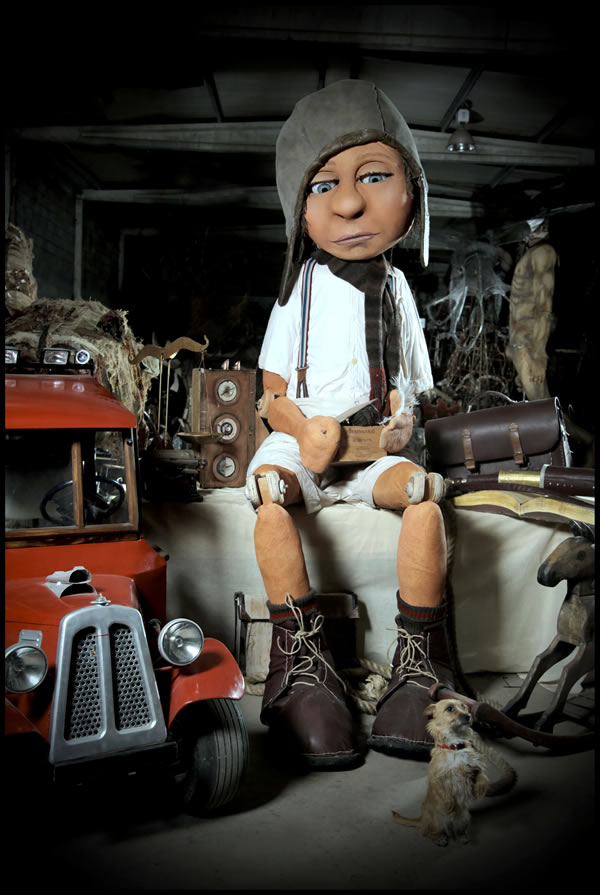

All of the parades come from a narrative - there's a whole story behind every single parade. The Boy Explorer was about what a lonely boy does; what isolation means for an 8-year-old. How do you magnify that and how does he meet friends, and how does that brings him back into the world? Crom is about hurt. He's an older generation. He's frustrated. He came from that Pagan idea of the God of Fertility and Destruction and he's been reawakened in the 21st Century, coming through the streets of Galway and he is hurt and he is wanting to express that and get it out of his system and go, ‘Who's around me to help exorcise this and where's the cathartic energy to release it?' The Girl Inventor was all about how do we invent a new way of being? How do we conjure up the imagination to get us out of this crisis that we were in in the country when we had a lack of leadership. Why don't we build a 13-year-old girl who's an inventor and what's she going to discover? A new universe, and what's that new universe about? It's about imagination and love - because they're the things that move and make change. It always comes from a poetic space.

When I go to the team, I've written up a whole story so that when the Performance Director and all of the public are coming in to get involved in our work, they all belong to a Macnas world. They know that Crom is the head of this world and they are all these characters and extensions that exist. There's a whole story that's made and then they populate the story and they animate it and then the audience are the connectors, the vital energy. The idea is that we create this whole pop-up book and the audience are turning the page and reading it as we move down the street.

Your favourite cultural city/place in the world?

I think Berlin has a lot going for it. It's a bit of a rockin' town and I also think Valencia in Spain just kicks ass. I love Spain because they have these demented, brilliant, crazy, honky-tonk festivals all over the country where stilt walkers run down mountains and they blow up Jesus and nobody is upset, and they build fucking efigies the size of Europe and burn them with two-year-olds lighting the match. What I love about Spain is they've got this great combination of chaos and containment, religion and fire and they just seem to hodge podge it all in and just keep evolving and creating madness.

But I also look at Galway as a pioneering city. When you think about Ireland 30 or 40 years ago - there was this hive of artistic inventiveness happening on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean and you think about how that's been built up. And it hasn't even reached its potential; I feel like it could go panoramic in so many different ways. But I think we could take a leaf out of Nantes book where the Mayor of Nantes invested €9m in Royal De Luxe, which is more or less saying, ‘culture first', because culture is at the heart of everything we do. Whereas from a governmental perspective, we're still sidelining culture as a kind of lovely thing, an entertaining thing, but not understanding the power or the potential of it.

You get the feeling when you're in Galway that this hive of culture has been here forever, but it hasn't. So in the past 30 years, what impact has culture had on Galway as a city?

I think that culture has absolutely given Galway an identity that has been recognised across the world as this innovative, exciting, amazing, beautiful, interesting city that is just populating itself with energy, diversity, newness and creativity. Thirty years ago that didn't exist, but 30 years later we have a whole new generation of artist - this hybrid, amazing, bubbling energy of youth in this city. So we need to get behind them and afford them the opportunity to get up on the platforms that we have created to evolve and develop and bring this city and its cultural story and sensibility into a new and amazing and bigger and better and wider and more chaotic and more engaged cultural city. We need to find a way to support and develop and keep these creative new amazing inventors to allow them to deliver and develop a whole new creative and artistic sensibility that will move this city forward.

So what's your vision for Galway as a cultural utopia?

I think that again, we need to readdress the balance between how we see the role of culture. It needs to be taken seriously. It is not about hotel beds, it is not about clowns getting dressed up and going out and being funny. It's about an absolute essential societal, structural, important, catalyst to basically move education, to move communities, to move politics, to move how we see and who we are into a different realm. You break culture down into its components - who doesn't like to listen to music? Look at how music has been involved in evolution and revolution. It's the same with writing, it's the same with poetry, with traditional music, it's the same with our indigenous language. These are all essential core elements to the existence of humanity. People prick up their ears and feel connected when we use creativity as a tool to explore, develop and evolve. That's obvious to me, so why that isn't taken on as a remit to develop our consciousness and possibility as a nation always amazes me. Creativity involves such a hybrid of person, of thinking, of difference, of problem solving, of trying to make some things out of nothing and trying to conjure things up to connect and communicate with people. I feel it needs to be repositioned onto the main central stage of fundamentally how we run our country, because with those kind of concepts and ideas, new industries emerge. I don't think there should be a separation between government funding and art. I think it's a no-brainer - like health and education; it's the same. Just as much as we need nurses, teachers and dentists, we need innovators and artists and creators.

What would that look like for Galway?

We could pioneer so much. We could be the city that houses a new amazing educational system where the best and the brightest are emerging from. There could be collaborations between business and arts in a way that's not just one giving money to deliver the other, but actually a symbiosis and a synchronicity and new inventions and new visions. You could look at how the demographic of the city could evolve, how geographically we could pioneer the most amazing living suburbs and scenarios for our children and our grandchildren to grow up in. The fact that people would have confidence, energy, openness, vision and innovation. It is constantly rejuvenating and reimagining how we live. I think the possibilities are endless. If you were to put culture as the main proponent to how you develop a city and society - I think it's not a ridiculous thought - it's a healthy, wonderful, amazing possibility-bubble of perpetual brilliance.

- Stephen Walton - Previous

- Next - John Crumlish