Garry Hynes – Artistic Director

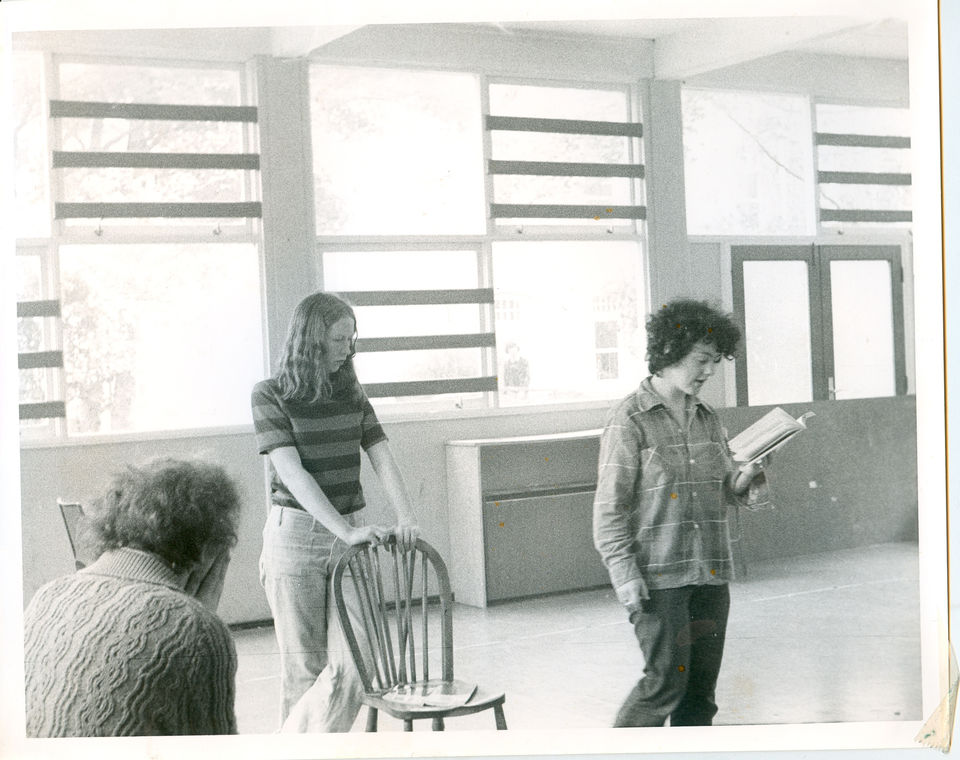

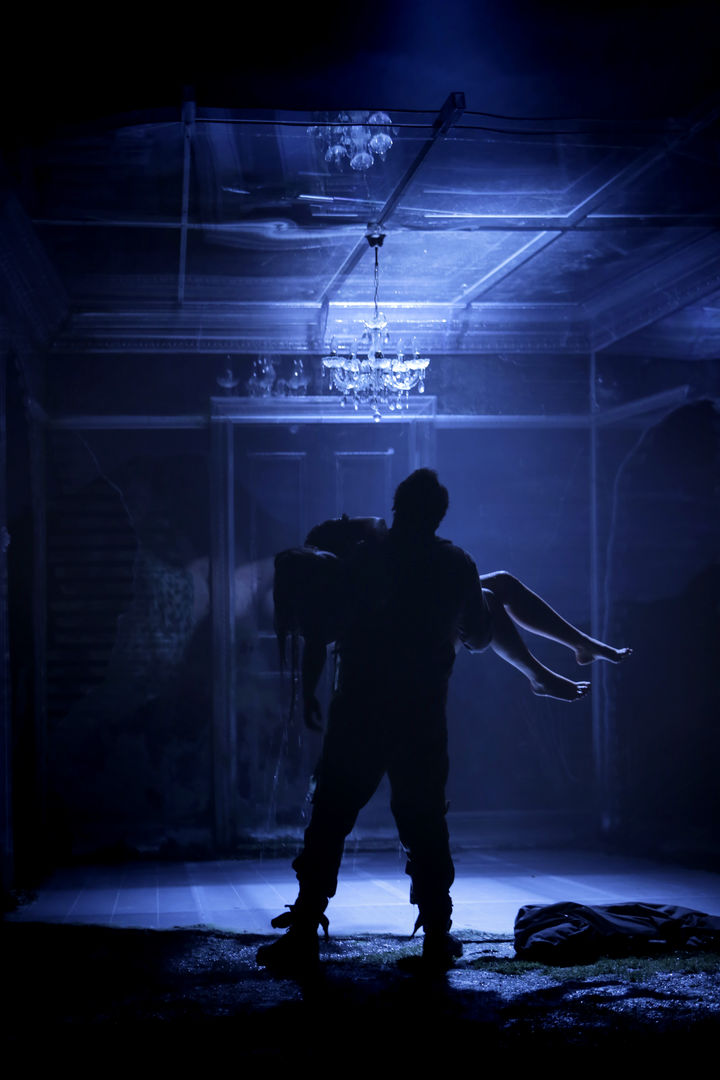

Garry is co-founder and Artistic Director of the Druid Theatre Company. Apart from a 4-year stint as Artistic Director of the Abbey Theatre in the 90s, Garry has been the Druid's Artistic Director since the 70's.

More from...

Can you tell us a bit about how you got to where you are today?

I was born in Ballaghaderreen in Roscommon and moved to Galway, where I went to school in Taylor's Hill and then on to UCG, as it was known. In my final year there, I founded Druid Theatre Company. I left in 1990 and I became Artistic Director of the Abbey. Once I left I had thought, as had everybody else, that other than working for Druid as a director from time to time that that would be my only association with the company, because I left entirely; I didn't stay on the board or anything like that. But then I was invited back by the board four years later. They had difficulty appointing a successor to my successor, which was Maelíosa Stafford, and they asked me if I would come back on a consultancy basis for a short period of time...I'm still here.

Did it feel a bit like coming home to you?

It did. I was very unsure about it and I think the board were very unsure about it because there's an old phrase, you can't go home again. I wasn't sure at all about it but in fact, it did work out. Probably had I not left then, I would not be here now. I think it was possible for me at that time to appreciate Druid's merits from a distance, and also, while understanding the past, feel less dependent on the past because I had gone away from it. So I think certainly for myself, and for Druid, it was an odd way of doing things, but it's worked out - most of the time.

What do you love about Druid?

It's very difficult to say what I love about something I'm this close to. It's not so much what I love about Druid as much as Druid is both a part of my life and yet something quite separate from me - that's what it feels like. What I love about Druid is, I suppose, the sense of the West of Ireland. What makes me proud is when other people who work with Druid are proud of it and when people say that working here offers them an experience unlike their experiences elsewhere - that it's special, that it's different, it enables their work and helps them be true to themselves in their work. I suppose those are the kinds of things that I would like to think are part of the Druid spirit.

You've been cited as one of the founding members of the arts scene in Galway - what was the driving factor back then?

The driving factor, we were very clear. Myself and Marie Mullen and Mick Lally and the other people who were involved in those first couple of years were very clear that we wanted to make a theatre that was about our lives in the West of Ireland. We were very clear that the West of Ireland was at the heart of everything we did, so when people suggested that we do a play that had been a hit in Dublin, we'd say, 'No, if it's been done in Dublin, we don't want to do it'. We were very very clear that what we did was going to be, inasmuch as we could make it, different from what other people were doing, because living in the West of Ireland is different to the way other people live. That's always been the way.

What was life like for you at the time?

As young people at the time, we lived a fairly hand-to-mouth existence, but it's easy to do that when you're young, and you don't have obligations and so on, so we made everything ourselves. Mick and Sean McGinley and people like that built the sets, Marie managed the money. Everybody did everything and if that's the way young companies start out, then I think it's reasonably easy to do it. What gets difficult is to make the transition from that kind of sense of community to becoming a professional organisation without losing the spirit of the community that was there in the first place - that's the tricky task.

At the beginning was it something you took very seriously or was it something you were doing for fun?

We took ourselves extremely seriously, from the very beginning, which is not to say we didn't have lots of fun along the way, because you have to, but we were very serious about what we were doing.

How would you describe yourself?

I may as well use my Twitter description which is theatre director, aunt and general enthusiast.

What drives you?

If you asked me that question 40 years ago, I might have answered it very differently, but right now, what drives me is the simple awareness of how extraordinary it is to be alive and to make every second count.

Do you work on instinct or do you think things through?

I do both. I pay attention to my instincts, but then I'll interrogate my instincts as well. And then finally, particularly with the big decisions, eventually it's your gut that gets you over the line.

"...what drives me is the simple awareness of how extraordinary it is to be alive and to make every second count."

Who or what is your greatest influence?

In the first instance, probably my family - my mother and father, and then really the people I work with. The effect of somebody like Marie Mullen, the actors I worked with in Druid Shakespeare. It is the friendship of my collaborators which is the most joyous thing to me.

Is it like a family?

Yes, it is, but I always get worried when I hear people say, 'There's a real family feel here', because families can be terrible places as well, they shout and scratch and do awful things to each other. But I think there's a bond for the most part that happens and that continues. You see that when you meet somebody that you haven't met for a long time, or you see that in the renewal of friendships of people you haven't seen.

Your greatest achievement?

Staying alive.

What are you working on at the moment?

We're preparing for next season. We're working on all the things that are difficult to work on when you're in the middle of a big production like Druid Shakespeare. We're going to be celebrating our 40th birthday with a big event later in the year.

How does art and culture influence your daily life?

To ask me how it influences my life is to suggest somehow or another that it isn't an intrinsic part of my daily life. It is a part of my daily life, not just because I work in the arts in theatre but it's a part of everybody's daily life and absolutely has to be part of your daily life. Because we are not just economic entities. We're human beings, we love people, we love places, we are affected by places and by things around us. We respond to music, we respond to the beauty of place. I think art and culture are intrinsically some of the great privileges of being human.

Do you find you have to make sacrifices for your work?

Everybody makes sacrifices for their work in one way or another. One of the sacrifices the majority of artists make is an economic one. Quite simply, the economic reward for working in the arts, in the way I do certainly for working in the theatre, for the majority of people aren't great. There's a lack of job security, which I've suffered from far less than most because I've been employed by Druid for most of my life, but there are sacrifices. And as I said in referring to the early part of my life, it's easy to make those sacrifices when you're young. Where it begins to really hurt is when people get older, when they begin to look to having to take care of a family, when they begin to need security because others depend on them, and when they start to look to their old age. Those kind of things that people take for granted like pensions and so on, simply have not, until very recently, been part of the thinking of the majority of people who work in the arts in this country.

Why do you think that is?

The sector's so poor because the reality is that an actor will work for nothing or profit share in the early years of their career in order to do the job because they really want to. People wouldn't think for a moment of working without profit or pay in a lot of other jobs. One of the other things a lot of people don't realise is that everybody who works in the arts in effect subsidises it. So we think of subsidy as something that comes from Merrion Square from the Arts Council - it's not true. The majority of people, of really skilled and capable people, could be working in another industry for bigger financial reward and certainly for greater job security, but they don't, and by doing that they are inherently subsidising it.

Do you think that there is a possibility that it could turn into a young person's industry?

Yes, I do. I think that's a very good way of putting it. If you look at, for instance, obviously the arts has suffered savagely under austerity - there's nobody that's been unaffected by it. But if you look at the cuts to the arts, and the amount that's been cut out of an already extremely small industry, it means that people do leave it. I know people who have left in their 30s and 40s because simply they could not continue to sustain it. It's good fun living on bread and beans when you're in your 20s. It's not such good fun when you're in your 30s or 40s and it's not such good fun even if you're in your 50s or 60s and you're earning the equivalent of what you earned when you were 25 or 30. I mean, it's not good for the soul.

"People want to live in places that are good to live in, and arts and culture makes people feel good about where they live."

Where is your favourite cultural city or place in the world?

New York. I fell in love with New York as young student, a teenager, and I love the place. When I was a student, you either went to London or New York to work on the J1 visa. I went to New York and fell in love with it. I love the buzz. I love the fact that there's so much you can do, any film you want to go to, anywhere. Food is one of my passions and New York is one of my superlative places for food. And just the beat of it...

What impact do you see culture having on Galway City?

The Galway that I went to school in in the late 60s and early 70s was a sleepy backwater and culture has helped to transform the city. People want to live in places that are good to live in, and arts and culture makes people feel good about where they live. That is proven by statistics. When we opened the theatre here in 1979, it was completely derelict - the only time people came down was to go to McDonagh's fish and chips. I'm old enough to have seen the transformation of the city in some good ways and not so good ways.

What does it feel like to be such a part of that?

You don't think about it. You bore people with stories about the fact that when you were working on Sundays in the theatre, you'd have to make sure to make a sandwich at home because there'd be nowhere within a mile radius to get anything to eat. But you live in the moment, you don't live in a series of images of the past.

Do you feel proud about your involvement of the development of the arts in the city?

Of course, I'm very proud of it and I'm particularly proud when people are good enough to honour me. For instance, getting the Freedom of the City was very special to me, and getting the honorary degree from NUI Galway made me smile, because I barely got out of the place with a BA degree and yes, that does make me feel proud.

Are you proud of what Galway has become?

Yes, I'm very proud of what Galway has become. But there are aspects of that development that I don't like. I get very concerned about retaining the sense of community, which I think is important in all communities. I get concerned, and it's not just Galway that has this problem, I get concerned that at times, the place can seem simply a centre for tourism. In Galway, on busy days during the summer, it feels like some giant Disney version of the West of Ireland. I do have dark thoughts like that from time to time. I think it's really, really, really important to balance the need to have a healthy economy with the other needs of having a healthy life, a healthy sense of place and a respect for place, and simply even the geography of the place, the spiritual nature of the place. I think sometimes we don't get the balance right and if we continue to not get the balance right, we'll kill the goose that laid the golden egg.

How do you think we can encourage that?

I think all aspects of living in a community contribute to that. I think planning, thinking in the long term, thinking if we do that now, what are the implications not just in one or five years' time, but in ten years' time. I don't have children, but to think in the context if I did have children, what kind of a Galway do I want them to live in 20 or 30 or 40 years time? We need to make sure that we don't make decisions that in the short term, might be economically beneficial but in the long term, are leading to the destruction of the community. Right at this very moment there are any number of arguments going on in that context. I don't believe it's right that a commercial Hollywood entity should be filming on Skellig Michael. Perhaps because I'm one of the few people who've gone to Skellig Michael and have felt the extraordinariness of that place. The notion that the short term tourism gain is worth transgressing across that sacred space - I don't think the benefit is there. I think it's very important that all communities that have a healthy artistic sector benefit from that commercially. San Francisco is one of those kinds of cities and Galway is one of those kinds of cities. I think it's very important that what comes in the wake of that, which are the economic benefits, and all the businesses that serve that, are kept in balance with the needs of the arts. I believe the current decision in relation to the ring road in Galway is appalling, and I can't say other than that, particularly since it personally affects me.

What's your idea of a cultural utopia for Galway?

I think everybody has identified the absences - there is an absence of infrastructure. I think that Galway 2020 and the energy that's being put into the bid is terrific, not only for what it will do for Galway in the wider context, but even as a reminder to those of us who live here how special a place this is and how important it is to protect it and nourish it and be aware of it.

"I think it's really, really, really important to balance the need to have a healthy economy with the other needs of having a healthy life, a healthy sense of place and a respect for place, and simply even the geography of the place, the spiritual nature of the place."

- Finbar 247 - Previous

- Next - Aislinn Ó'hEocha