Marc Mac Lochlainn – Artistic Director, Branar

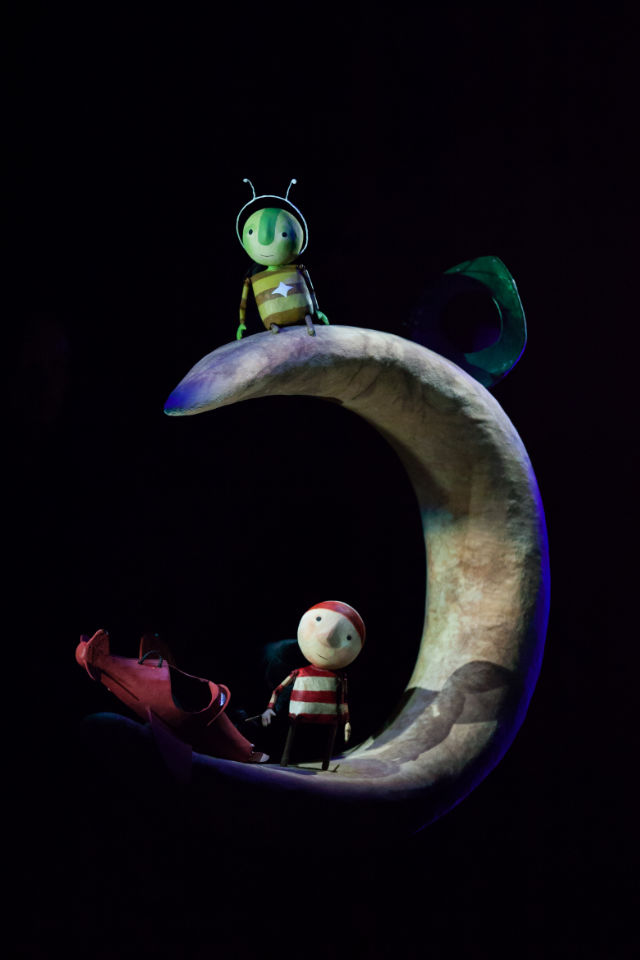

Marc is the Artistic Director of Branar - Theatre for Children through Irish. Branar’s mission is to produce a 'simple, elegant form of theatre for young people, that achieves intricacy through the creative use of few means'. Branar has recently toured The Way Back Home in Japan, Denmark and France.

More from...

Tell us a bit about yourself?

I am from Kildare; I'm a farmer's son, and I studied in St Pat's in Drumcondra in Dublin. I wanted to be a primary school teacher. When I was studying there, I ended up coming to Galway and working out in Carraroe in the Gaeltacht - that's how I got to know Galway. I was working through Irish and I really loved it; it was completely alien to a lad from Kildare to be able to work through this language. It just came naturally to me; I was suddenly remembering everything I learnt in school. I went to the Gaeltacht in 5th year and then after my Leaving Cert, I went back again and started to work there as a cunteoir, and I spent 13 summers in Carraroe. When I was in St Pat's, I studied Irish and did Human Development, which is a mixture of psychology and sociology, but it was all very child-focused. So I was always really interested in working with children and thought that teaching was the obvious way to go. So I applied to do a postgrad in teaching, and didn't get it. Then I spent a year teaching primary school - I was delighted I didn't get it then. I loved dealing with them, but there's just too much minding involved and when you're 21 and a lad, you're not very maternal. I then came to Galway to do a H.Dip and I haven't left.

My interest in drama began when I was in college. The first time I went on stage was when I was in St. Pat's. I joined the Irish language drama club, as you do in college, and I thought, 'I kind of like it up here', so I kept doing that while I was in college.

After I did the H.Dip, I got into Coláiste na Coiribe and taught there for two years teaching Geography and CSP (Civic, Social and Political) through Irish. When I was there, I was using a lot of drama and I had also started work in the Taibhearc, so my work in the Taibhearc and my work in Coláiste na Coiribe were happening parallel.

Branar came about when I was looking for people to come in and do workshops for the students that I was teaching, because they were probably thinking that this was some crazy stuff that only Mr Mac Lochlainn does, and I couldn't find anyone that would do it through Irish. So that following September, I got in my car and started to do workshops in schools around the country.

What did the workshops entail?

It took me a long time to figure out what I was or what I was doing. It began where it was very much curricular-focused. I was doing workshops for secondary schools where I was doing drama methodologies to bring the poetry curriculum to life, or take a play that was on their course in Irish and doing workshops or a story with that - just a way to bring life to it. I was doing this while I was teaching and suddenly, there was a market for it. I was doing maybe 60 schools a year, constantly driving my little car around the country.

People were really open to it then?

It was kind of subversive in that I was getting in under the Irish language umbrella, but I never had an intention to teach Irish; it was more about getting them to do drama workshops. It was the best education I could ever have because I was meeting different kids every day and dealing with all-boys schools, mixed schools, all-girls schools. You have to learn how to handle groups, and you learn what interests kids - what triggers their imagination and what doesn't. So Branar evolved from then. Coming up to 2004, I was doing a lot of work in secondary schools and I was also doing a lot more professional acting in the Taibhearc - I was mixing both of them, which suited me perfectly. I was asked by a teacher if I'd do something for primary schools and I felt that I didn't know enough about that age group yet. So I went and worked with Graffiti, which is a children's theatre company down in Cork, for about six months on a show and then I came back and did a one-man show in libraries. The following year, I hired my first performers and we did a show. I wrote it, we devised it together and we brought it around to schools in Galway. I'd hate for anyone to see that show now, but it was something that needed to happen because nearly every idea that has happened since was in that show - it was a mish-mash of everything I wanted to do. I gradually figured out that this was the stuff that I wanted to do, and then by doing it and by working with really good people, I found the way I wanted to tell stories - I found out why I wanted to tell stories. Then we honed it so that we work now for 0-3 or 2-6-year-olds, and other really focused age brackets.

And you do lots of travelling?

Well, I don't. I'm like the guy in the factory waving at the lorry. We have a lot of co-production partners, but I've got better at saying that if we're doing a co-production, it has to happen here. That's working out better, I don't really want to be away either; I have a family. But it's nice to go and see work in other places. I remember when I started to travel to see festivals and saw work in other languages, that was a real education because you realise that that's what it's like for people who have to look at our stuff. Language isn't so much of an issue - kids don't care, but adults do. If you mention the Irish language to adults they go, 'Oh, I don't know if we can go', but children don't mind. The show Spraoi that we do for ages 2 to 6, that's in Irish and Catalan and no one bats an eye. Every language is the same for a child that age - they're still learning everything and they speak physical language, so they'll read it rather than listen to it. I've learnt that when we build a show, we build it in layers. Children are different - you can't look at a class and say, 'All of you are going to learn like this'. Everyone has their own way of learning and that's the value of the arts for children is that they can find their own way in. Whereas when you look at a textbook, there's only one way to look at it, there's only one way to work with it. With the Arts they can say, 'Well, I like to listen, or I like to make or I like to paint or I like to play or I just like to move - everybody has their own way of getting around it. I'm always conscious of that when I make shows - as much as we can, there's live music, there's puppetry or some kind of object element to it. The body language is quite physical and the oral language is as sparse as it needs to be. Together, it should be like a poem, but when the kids are watching it, they'll find their own way - they'll just listen to it, or they might just pick an element now and again in each layer of the story.

Where do you get ideas for your plays? Do you write them all yourself?

I wouldn't say I write them, only recently have we started writing stuff down. Normally, what I'll do is I'll just take an image and just say, 'I wonder what will happen if we just look at that image and see what the story is of that image'. That's where most of the ideas for me start. It's very visual in the way that I look at it. And you keep pulling away at it until you find a story. I love illustrated story books. We've done one of Oliver Jeffers already and we're going to be doing one in a couple of years; we've just got the rights to How to Catch a Star. I love those kinds of sparse images that say loads.

So how does it work technically?

I'll have an idea of something I want to do and I find the right person, or it's the right time, then we'll do it. When a story is flat on a page, it's one sort of story but when you bring the characters to life and you build a world around them, you need to know a little bit more information. That's where our work comes in - it's to build the lives of these characters. I'll generally spend two years on a show before we open it to the public, but over those two years we'll probably spend maybe 20 weeks of actual rehearsal. So it's two years to cook - the story might change, but you leave time for it and you leave time for asking as many questions as you can. We have a big responsibility as people who make work for children because you can't be guaranteed that that child is ever going to see a show again, or has ever seen a show before. If this is their only chance to see something, it has to be absolutely perfect. We spend as long as we can asking as many questions as we can to make sure that when they watch it, they don't have any questions - it flows for them. At least if they never see anything else again, at least they saw something good, and we can stand over it.

Is that how you gauge how successful a show is?

Well, if they ask questions that we haven't asked already or if they ask questions that we don't know the answer to, then that's a problem. The problem could be that you've given a signal that there's a move that's wrong or a pace that's wrong or a light is giving the wrong signals. Kids are so scrupulous in the way they looking at things. When adults go to a show, they could be hating it but it's behind the smile - they leave and give out about it, but they don't give out there and then. Children applaud with their silence, so if they're sitting and they're watching, they're with you. They give you appreciation all the way through - if they're with you and in the show, then you know it. There's nothing nicer than sitting in a group of children who are completely engrossed in what's happening and that's how we know - especially with three, four or five year olds. You can't really talk to them about what they've seen - it might take them a couple of days to assimilate it and give you back the information. It's the shuffling bums and the looking around that lets you know that the moment isn't enough for them or that it's too much, so you get rid of it. That's how we do it. As many times as we can in the rehearsal process, we bring it to schools and we show children what we've made and we gauge it along the way so that they're co-creators in it.

What's your overall vision with Branar? What do you want children to get from the shows you produce?

If they go and see a show and they come away from it with a sense of having been part of an experience. It's not something like going to the circus - it's not an immediate euphoria. It depends on the show, but they should be moved in some way. What we try to do is tell stories that aren't Disney, because kids lives aren't Disney. There might not be a happy ending, but at least it's genuine and it's authentic. There are no stories for the ordinary people, so we try to tell stories that are real. We've told stories about bereavement, a lonely old man, and kids are genuinely interested in it; they're concerned more than we are for their community and we try to catch onto that.

We want them to enjoy it, but we don't want them whooping and hollering all the way through the show - it's lovely and so rare for children to be able to sit for 40 minutes in silence and be part of something. Everything now is just thrown at them, and it's bright colours and dancing monkeys and they have no choice but to be whipped into it.

So what is it that you most enjoy about what you do?

I love making work for kids. When I see work for adults, it doesn't fire my imagination at all because I think we accept too much as adults. For children, you have to really push the boat out with the creativity and the imagination, and you have to find little bits of magic in everything. They give up on that with work for adults - I know that's just broad strokes, but with children's work, you just have to work that bit harder and especially so when we work in different languages. It means you're really forced think, 'Is this clear?', 'Is there enough?', 'Am I going to hook the audience?', and each moment has to be valid. We constantly get letters from kids who have seen shows just picking out their favourite part. I just love doing it - it's not for the money anyway!

You obviously have a very vivid imagination - you must have read a lot when you were a child?

No, I didn't. But I grew up on a farm and when you grow up on a farm, there's work to be done. You're outside all the time and you're working with nature, you're working with animals. There's a constant invention that's needed. You're constantly having to invent ways to fix things, and it's a side of my brain that I love using. Part of the reason I love making work for children is that I get into the workshop with the lads and we get to play with ideas and make stuff. I just love the idea of taking an image and making it come to life - seeing what was behind it or what's after it.

You use such beautiful puppetry - who makes them?

We have this brilliant puppet-maker called Suse Reibeisch. She's fantastic - she's made up all the puppets we've ever used, so she's key to everything. I met her here in Galway years ago and now she lives in Mayo and makes puppets for us.

Describe Yourself?

I suppose I love messing - I'm a messer and I get to be playful in my work. Not everyone gets a chance to go to work and play, or to send an email to someone saying, 'Do you want to come play on this?' It's like a play date, but they understand that it's a job. I'd like to think that I was creative. I like having a community of people around. I love that the performers who work with us really love working with us. They can invest in the idea that started with me, but it's become so much bigger than that now and I like that. I'm not describing myself at all!

Where do you see Galway culturally at the moment?

When you look under the covers it's a bunch of people working really hard, not getting a lot of support and just making these great things happen. You ask those people, 'Why are you doing it?', and they say, 'This is what we do, we'd do it anyway'. There's this little engine room of people that make a lot of stuff happen in Galway, that creates the reputation. We make really good use of very few resources to make all that happen.

With us, last year we performed more times in Japan and Paris and London than we performed in Galway, and we're working out in Ballybrit. There's nowhere for us to play. We have our own space out in Ballybrit, which is where we make all this work but it's not somewhere where you can bring the public. We're moving in the next couple of months to somewhere new and we're going to do shows there as well. My ultimate aim is to make a Centre for Imagination - somewhere that's made for children. We have this skillset that's untapped in that what we do daily and it's what industries look for. I'd love to have somewhere where we have all these people together and John from engineering can come in and say, 'We have this really big problem and we don't know how to solve it - I wonder if you guys could work with us for a couple of days and see what could happen'. I'd love to see how could we make something like this work.

What's your vision for Galway?

In Bologna, after the war, they had to rebuild the city and they decided they'd make it a child-friendly city. Every open space, every public space, has an area that could be a playground and because of that, the city has a fantastic creche structure, it has a fantastic education system, its artists are involved in loads of things with them. I'd love for us to say, 'Let's make Galway a child-friendly city'. We could have a painted channel for children and families to walk along on Shop Street, and in all of the restaurants, a children's menu with good food. There could be buggy parks, pop-up playgrounds around the city, people with buggies could travel on the buses for free. I think that for a long time, in Ireland, we haven't cared enough about young children or young people, and it's an attitude that feeds into everything in our world. So if you suddenly start to say, 'You know what? We care and we're going to do this for you', imagine the citizens you have when they start to vote? The pride, the sense of place that children would have from that. You just have to look at a really good school for an example. If children are treated with respect, and they are given the facilities, they love their school, and for the rest of their lives, they speak longingly of the time they were there. There's no reason that the city can't be like that.

We go to Spain on holidays and I love the thing where they just rub kids on the head and it says that they're not in the way - no one's telling them to shut up. Literally, all it would take is for Galway to be the first city council to sign the UN Declaration of the Rights of the Child and say, 'See this section here about their cultural rights and their rights to freedom, free space, play? Let's sign that'. It could be really easy. It might be a pie in the sky, but it's a nice one to have.

Updated: 24th March, 2016 with a minor change to a phrase used.

- Anne McCabe - Previous

- Next - Siobhán Ní Ghadhra