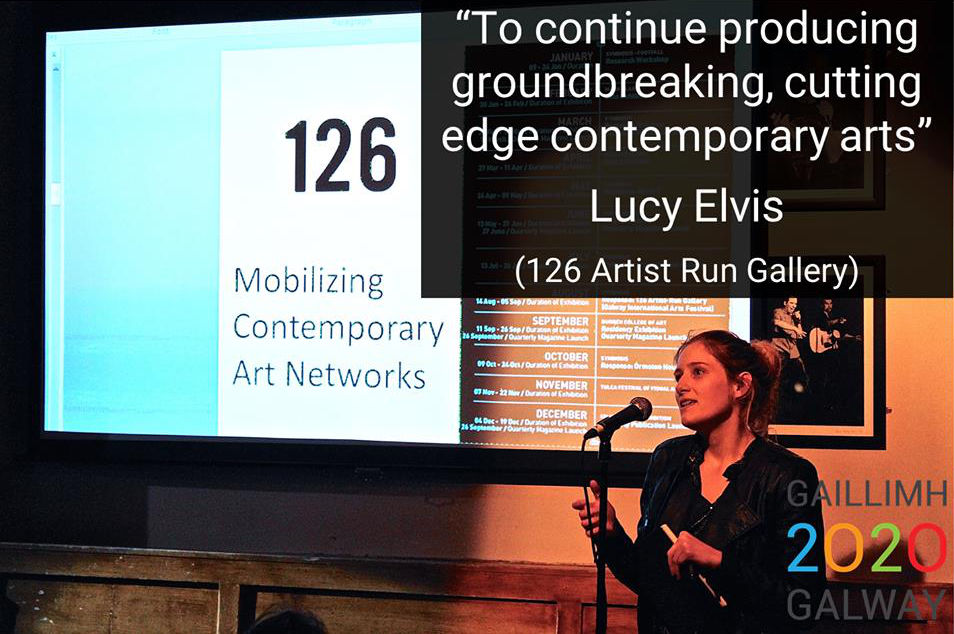

Lucy Elvis – Co-Chairperson, 126 Artist-Run Gallery

Lucy is the co-chair of the Board of Directors at 126 Artist-Run Gallery. She is currently undertaking a PhD in the Philosophy of Art and Culture at NUI Galway, and is also an arts writer

More from...

How would you describe yourself?

I'd be quite nerdy; I love doing my PhD. I'm a bit antisocial once I get into a research track of interesting things. I have a terrible habit of kind of glazing over during conversations at home because I'm thinking about something I read earlier in the day. I guess I'm very sociable. I really love meeting new people, which is an asset when you're trying to network for an organisation or on their behalf.

Are you an introvert or an extrovert?

I think when people meet me they think I'm very confident, but behind it, I'm very, very shy. I'm very good at foregrounding other people's ideas, but then if the spotlight is on me, I find it a little bit uncomfortable. I think that's why I like working in 126 - because it's a team and it's quite nice to be producing research because you're promoting the idea that you had rather than talking directly about yourself.

Do you work on instinct or do you think things through?

It would be so sexy to say that I just worked on instinct, but I don't, I think things through. In fact, I think things through sometimes to the nth degree to almost every eventuality and it can get rather frustrating, so it's nice to work at a team in 126 because there's a point at which someone will say, 'Let's make a decision and just go for it', which is great but when it comes to my own personal research, I like to pursue each avenue to see which one is going to work best. It's a time-consuming way of working, but it's rewarding as well.

Who or what has been your greatest influence?

When I first became really into architectural theory, which is what I'm studying now, I was really heavily influenced by my dissertation tutor at Bachelors level. He knew so much. I find people with loads of knowledge really fascinating, especially people who don't foreground it in a way. My grandad is very like that - he's 87 now - but every time I talk to him, he tells me some other thing that he's been interested in or has a level of expertise in. Stage sword fighting was the last thing I found out about. He worked in a tool factory, but he used to just have an interest and then pursue it, for no other reason than to gain more expertise in it. So he was a raleigh car navigator, he used to do fencing, he learnt Spanish at one stage, when he was 70 he started to learn the guitar, he sings really well, he's joined a choir recently. Last time I spoke to him on the phone, he sang me Jessie J down the phone 'All About the Money'. Hearing my 87-year old-grandad say 'Che ching che ching, not about the ba bling ba bling' is a great experience. So he's a great influence on me because he just adapts so well and so sensitively and carefully to things that are around him - he's open to new experiences all the time.

It's a bit cheesy to say my grandparents inspire me, but they're inspiring people - they have a big family, and despite the fact that he's 87 and my granny is 86 and blind, they can still call me on Facetime and talk the talk. They dressed up as Sharon and Ozzy Osbourne at my 21st birthday. They're quite traditional in a way, but they're very open to new things, new interests and going to new places. And they love Galway. They came here last year and said it was the best place they've ever been to, bearing in mind that they've been to places like Palestine and Italy and America.

Your idea of happiness?

I used to love going to festivals and stuff but my idea of happiness has become much more scaled down recently. Now it's just as simple as a really good cup of coffee, a really interesting philosophy book or a book about art or something, reading on the beach, having a dip in the sea.

"Culture isn't just a celebration - part of that is self-reflection, thinking about what ideas are prevalent, whether they're right, how long have we held on to these traditions and are they a good idea?"

How did you get involved with 126?

One of my friends was on the board but found she didn't have enough time to commit to it and asked me to join. She knew I had worked at a gallery in Sweden, where I did my MA, and had been doing work with Tulca. So I went down, met them and started tentatively. I only came on to help with PR and some of the funding applications and ended up doing a lot more different things. I got stuck into it really quickly - it's so nice to be in that kind of network, doing things and hitting the ground running. So I ended up being the chair with Marcel Badia and it's going really, really well.

How does 126 work?

It has a special constitution that's based off the structure of the Transmission gallery in Glasgow, and was also taken on by Catalyst in Belfast. Catalyst has been there for 21 years and Transmission's been there for 30 years. I went along to a talk about cooperatives and collaboration during the summer where I spoke about how 126 works as a cooperative. I was just about to stand up, when I thought, "It's actually something that shouldn't be there at all". The organisation is not-for-profit, run off the time of volunteers, who are also professionals. It is still be able to pay artists and still function as a professional gallery space - it's a contradiction in terms. I was saying to these people, 'Well, we don't make any money, but we do pay the artists, but we don't pay ourselves, but it somehow works because people are just committed to the ideas behind it.'

So what happens is people come onto the board, they commit two years of their time and after that two years, they have to step down. It's the idea that the gallery will stay really fresh - there won't be one person dominating. It has to be a democratic organisation, so although myself and Marcel are the chair people, it just means that we have a general oversight of how the gallery is running and what projects are coming up. It means I represent the gallery on the board of TULCA, for example, but it's really in a representative capacity. Any decisions that are made have to passed democratically through the board of directors. It has to be a majority vote, which is tough at the moment because there's six of us. So when there's a 50/50 split, it takes ages to get a consensus.

So what about exhibitors?

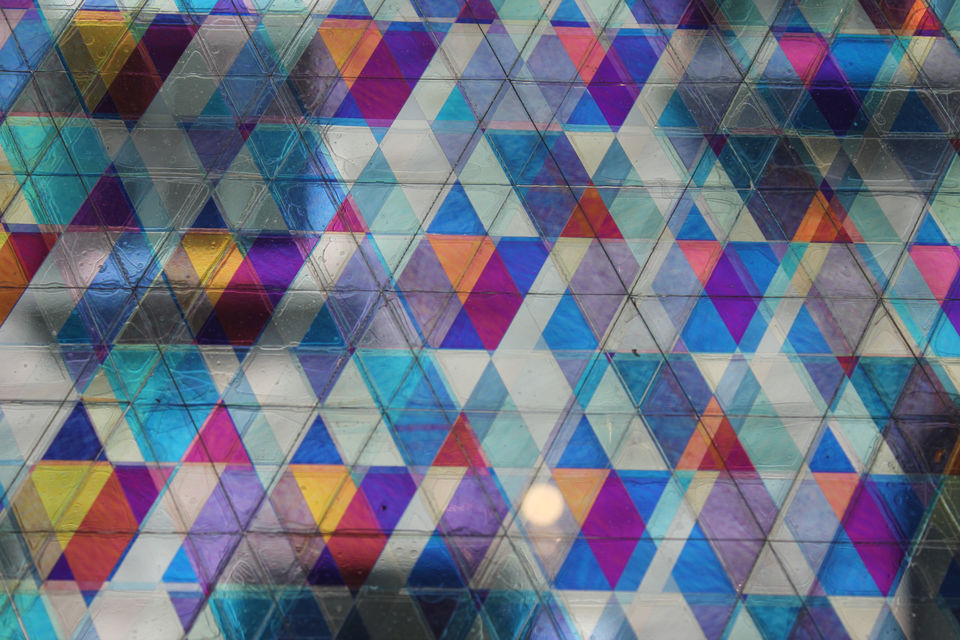

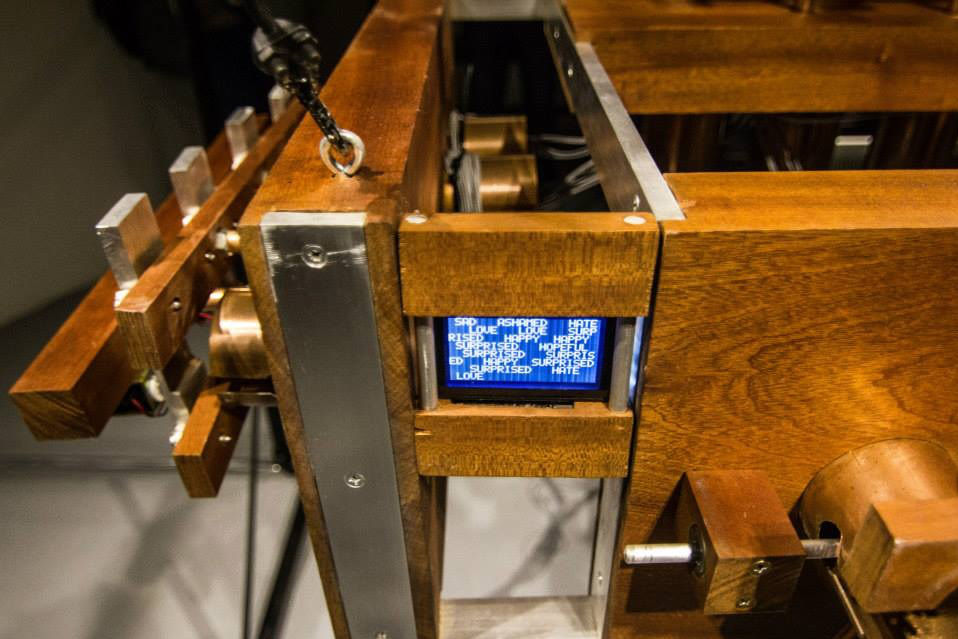

Our mandate is to support contemporary art that isn't commercial, so it's art that should have a platform; it's good, but perhaps wouldn't get exhibited in a commercial gallery because it may be performance art, it may not be immediately saleable, it might wrestle with difficult ideas or it could be from a strange practice point of view. The point of 126 is to foster an exhibition space and to create an artistic network of people who otherwise would not be supported in a commercial network. Those kinds of art for us are really important because they tend to be making a comment on the way society is and those things can be difficult to see or hear. So, having a platform for those kinds of artists where others can come in and see their art in a space that is free to visit, that is friendly, where there's someone there looking after the art that's passionate about it...it's really, really important.

I think in the place that Galway is in now, 126 has a good role to play when thinking about what culture means for the city, because culture isn't just a celebration - part of that is self-reflection, thinking about what ideas are prevalent, whether they're right, how long have we held on to these traditions and are they a good idea? Or - how do we see ourselves and our cultural make-up? I think contemporary art has an interesting role and an unfortunate tendency to be seen as somehow elitist or aloof or strange and that's not what it's like. I love 126 for its friendliness. A friend of mine took her daughter in there during the summer; she had been in the library, they did some colouring and they came into 126 to see an installation about colour by Sofie Loscher. We had a new volunteer invigilating and he took my friend's daughter around the exhibit, explaining how it was made and how it worked. She said she couldn't believe that she had never been before, that it's free...and now it's just a place on their route around town. It's somewhere to go to see something different. That's just the point of the gallery - to create a network for artists to help one another, support one another and provide opportunities for artists who otherwise would graduate from college and perhaps have nothing or nowhere to go, especially in this economic environment. With 126, they can exhibit their work, have a public platform and be paid for doing so. Because lots of public spaces might put on the work that graduates produce, but they would say, 'Well, it should be enough that we're giving you a public platform', but we think that all artists should be paid.

Where's your favourite cultural city or place?

I love going home to Birmingham. I think it's heavily underrated as a cultural city - it's really diverse, it tries really hard to celebrate all its cultures in equal ways. They celebrate Diwali, they celebrate Eid, Ramadan, Christmas, Chinese New year - so it's a fun place from that point of view. It was also a great place for me to grow up because there's three galleries in the city - a contemporary art gallery, which has the biggest collection of Pre-Raphaelite art in Europe, there's a centre of studios called the Custard Factory just outside of town and that's full of new artists that have open studios that you can go and visit. So it was a really exciting place to grow up. And other than that, I loved living in Sweden; I found Malmö to be similar to Birmingham that way - it's a post-industrial city with a diverse cultural make-up, with loads of free galleries that you can go and see lots of interesting small projects happening at a grassroots level.

What impact do you see culture having on Galway City?

When I was first going to come here [Lucy is originally from Birmingham], I heard that it was a really arty town. I was shocked that Gallery 126 was the only gallery space, apart from the Arts Centre. The Arts Centre does great work, but they don't have exhibitions all year round because it's a different kind of space. So it's strange, because before you move to Galway, the perception is that it's a really good town for art and literature and music. Music really thrives here and it's great to be able to go to the pub and listen to a mix of traditional music or go to the Roisin and hear brand new emerging bands - that's great, but I think visual art sufferers in a way and it's ironic, because there's a really massive department in the university that's studying aesthetics, there's a fabulous art college that brings out great graduates and where do they go? It's sad that there's not a municipal gallery in the city, but I hope that will change. There could be really great creative exchange between a municipal gallery and a non-institutional gallery such as 126 in the city - that in itself could be a really creative juxtaposition.

From your perspective, what would be a cultural utopia for Galway City?

It's hard, because a lot of contemporary art comes out of problems in society or issues so if you had a cultural utopia, it might cease to exist. But it would be nice to see a municipal gallery space in the city that was always changing and that had a board of directors that weren't necessarily just city administrators - you'd want to see half of those people being creative practitioners, whether they were curators, writers. It would be nice also to see a few more crossovers between the thriving writing community and the visual art community - it's something that we're trying to work on at the moment at 126. We're producing publications this year and next year, we're going to try to organise some residencies that pair visual artists and writers. But it would be really nice to see more of those kinds of creative collisions as well.

Galway has so much to offer already in terms of the festivals that happen, but there's a lot of hidden labour that I don't think people realise is there. There's so many people that give their time for free and perhaps we need to be honest about what that means for these people, because for some people, it means sacrifices in terms of their career. Maybe they're doing professional jobs but not receiving any kind of financial reward for it. In the private sector, you'd think that's insane and in the cultural sphere, that's OK or it's not talked about because it's not cool to talk about money if you're talking about creativity - the two things shouldn't go together. But if we highly prize those things in our society, then it shouldn't be a question as to whether or not these people are paid for work that they do.

- Olaf Tyaransen - Previous

- Next - Daniel Ulrichs